The shadowy part of the story of the Tengiz oil filed that, today, belongs to Kazakhstan does not end with James Giffen’s bribery case. Giffen, a financier, a spy and simply a fixer, was just one of the pieces in the big oil chess game played around the Caspian oil.

Nowadays, Kazakhstan is clearly experiencing the civil society’s fatigue with the First President of the country. However, this has not always been the case. During the last years of the USSR existence and the first years of Kazakhstan’s independence, Nursultan Abishevich Nazarbayev was one of the most advanced, active and efficient politicians and statesmen in the post-Soviet space.

With that, he was not only able to meet competition among the people that chose to move to politics at the time but also managed to achieve the best results (from the personal standpoint) – he had been the leader of Kazakhstan for 30 years, received the official title of the “Leader of the Nation”, has obtained the lifelong political immunity and has become one of the richest people, if not in the world. than on the territory of the former USSR for certain.

To a large extent, this was possible because Nursultan Nazarbayev, on one hand, has an extremely well-developed political intuition, on the other, is abnormally unprincipled, is able to betray his allies and associates in the right time, can maintain the balance both inside the country and his own environment as well as in Kazakhstan’s external ties with the leading world’s states.

Currently, kz.expert’s analysts are preparing a special report on the “Leader of the Nation”, and now, as part of this project, we are offering the material devoted to one of the key moments in Kazakhstan’s history when Nursultan Nazarbayev made not simply the right but the crucial for the country and its economy decision and brought it to realization. We are talking about attracting big foreign investors (including those from the US) in the Kazakh oil and gas sector.

The statistical data shows how justified Nazarbayev was in making this decision. Based on the results of 2018, Tengizchervoil LLP is the country’s biggest taxpayer (1.951 trillion tenge which constitutes about a quarter of the total tax return to the state budget in 2018.). On the other hand, this coin has a flip side.

The Diabolical Sulphur

The Caspian oil was one of the reasons for the collapse of the USSR. One comes to this rather surprising conclusion when studying the CIA classified documents that have become available as a result of the US program of declassifying the state materials (we have already written on this in our articles Why did Nazarbayev Go to Clinton in 1994 and A Spy at the Superkhan’s Court (text available in Russian). These declassified materials present an unattractive sight of the Soviet world that is hard to discern in the Soviet sources.

The CIA analysts noticed that the growth of the oil extraction rate (the main source of the Soviet state’s wealth in the 1960-1970s), first, started to weaken and, then, stopped completely. As a result of the draining of the old deposits, in 1980s, the growth rates of oil extraction started to decrease. The new oil fields had to compensate for this drop while the development of the three new high-potential oil-bearing regions – Barents Sea, Sakhalin platform and the Northern Caspian – were to cardinally change the outlook of the world.

The last project was particularly important for the USSR since it was to replace the oil deposits of the Volgo-Ural region. Once, this region was called “the second Baku” having played the critically important role during the times of the first five-year plans and the WWII. In fact, these deposits saved the Soviet Union by providing the country (from the start of the extraction in the 1930 to the 1980s) with about 40 bln barrels of oil. Now, it was the Caspian’s turn to play the role of the savior.

For the Soviet Union, Tengiz was to become not only the source of energy but also of the so called “freely convertible currency” needed to buy the equipment and consumer goods and to plug the holes in the Soviet economy suffering from the problem of the chronic deficit.

The CIA analysts thought that the hopes of the Soviet planners were unjustifiably high but deemed it possible that, by the start of the 21st century, the Caspian Lowland could be providing about 2 mln barrels a day. By the ratio of the beginning of the 1980s, it constituted no less than 15% of the total oil extraction volume on the USSR territory. However, the USSR could have brought these plans to realization only with the technological support of the Western business. By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union did not have the technologies and expertise to extract oil in the new oil-bearing regions.

Oil workers of Tengiz. Photo from the book “Kazakhstan’s Oil. History through Photographs”

Sulphur was the main difficulty encountered by the Soviet oil workers when working the Caspian fields. Such oil (with large quantities of sulphur) is called “sour” in the parlance of oil workers. It creates a very aggressive environment and working with it requires more resilient materials, equipment and technologies. The Soviet Union had none of that.

This did not mean that the Soviet engineers were incapable of creating them. But, as the CIA analysts believed, the sclerotic system of the Soviet management would have needed a lot of time to solve this problem. And the need for the oil and currency was urgent. The problem became political after the budget had lost the alcohol fiscal revenues and the oil prices had dropped dramatically on the world market.

The Soviet system could solve the problem of the technological backwardness via the usual practice, in other words, the centralized purchasing of the equipment and technologies – legal, semi-legal and completely illegal. The Soviet Union had actively used such methods and not just once. To control such purchases, the USA founded the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom). This happened in 1949 after the large-scale leakage of the nuclear-related materials had been uncovered. But, from the end of the 1960s, this mechanism grew weaker due to the start of the detente epoch.

At the beginning of the 1980s, amid the new “cold draft” related to the Afghan invasion, the USA decided to tighten control. The restrictions extended to the oil workers as well. To justify these restrictions, the US argued that a number of technologies could have been used for military purposes (the controlling systems, data transmission on a real-time basis and new resilient materials). As a result, the possibilities for the Soviet oil sector to catch up with the West in terms of the oil extracting technologies were reduced dramatically.

Given the Tengiz environment, this technological gap had led to the catastrophic consequences. In the literal sense of the word. In June 1985, one of the Tengiz wells was caught on fire (photo on the right) that was contained only a year later. And it was no other than US company Cameron that was able to do it. The estimated losses constituted $1 bln (6 mln tons of oil and more than 3 bln cubic meters of gas).

Given the Tengiz environment, this technological gap had led to the catastrophic consequences. In the literal sense of the word. In June 1985, one of the Tengiz wells was caught on fire (photo on the right) that was contained only a year later. And it was no other than US company Cameron that was able to do it. The estimated losses constituted $1 bln (6 mln tons of oil and more than 3 bln cubic meters of gas).

The weakening of the USSR’s standing led to the changing of the country’s line of action. Now, instead of seeking the new technologies, it was forced to search for commercial partners for its complex projects on the concession basis – participating in the profits from the entire project. This line received political support at the times of the perestroika. This is how Chevron happened to come to the Tengiz fields.

In 1988, the Ministry of Oil Industry of the USSR and Chevron founded a joint venture called Sovchervoil. Kazakhstan was not supposed to participate in the project. However, already in a year’s time, Kazakhstan’s participation became a matter of political necessity and Nazarbayev joined the negotiations that, from the very beginning, had been conducted on the highest political level.

FOR REFERENCE

Before 1984, Chevron was called Standard Oil Company of California (SoCal) and was the Californian branch of Standard Oil Co. Inc – the omnipotent Rockefeller’s trust that once completely monopolized the oil extracting sector in the US and fought with Royal Dutch Shell for dominating the world market. In 1911, the US Supreme Court made a decision that destroyed the monopoly, but Chevron managed not only to survive but to become a global-level corporation that operates in 170 countries today.

Chevron’s Share

Years later, Nursultan Nazarbayev would tell the story of how he visited the Chevron US enterprises in 1990. It was at that time, according to his own statement, that he chose the Californian company as Tengiz’ explorer. However, this statement seems somewhat exaggerated.

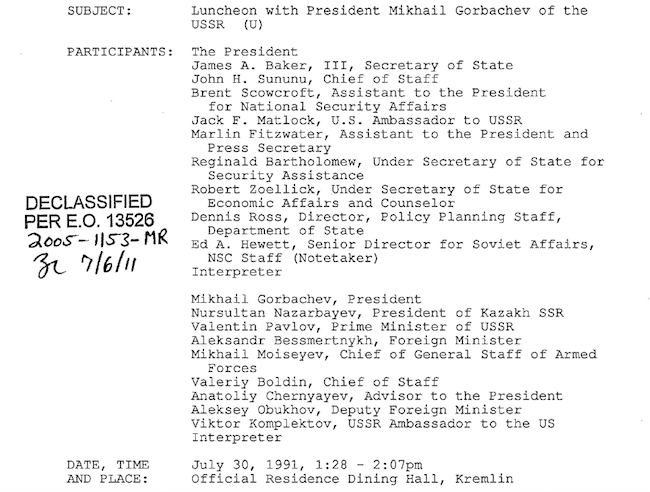

Up to the very collapse of the USSR, Nazarbayev acted strictly within the boundaries of the received negotiation mandate that was of a purely political nature. This follows from the declassified text of the record of the discussion related to the creating of the joint venture with Chevron. The discussion took place in the Kremlin on July 30, 1991.

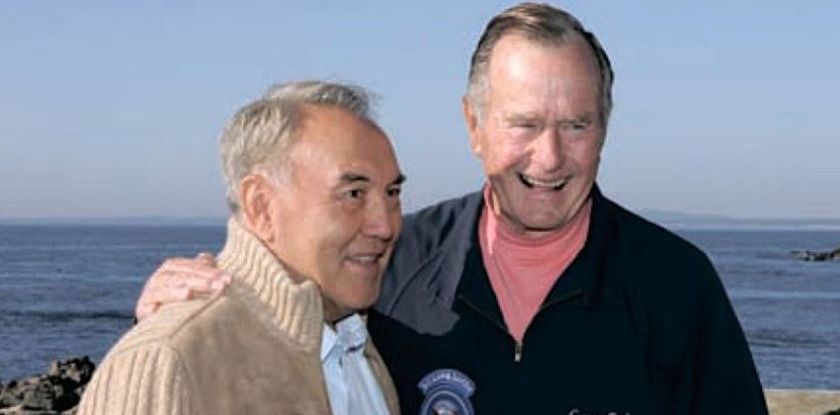

The list of the participants is quite dumbfounding. From the US, there was George H. W. Bush, Secretary of State James Baker, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Brent Scowcroft, US Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jack Matlock and a group of the NSA and the Department of State employees.

From the Soviet Union, there was President of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev, President of the Kazakh SSR Nursultan Nazarbayev, Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov, Minister of Foreign Affairs Alexander Bessmertnykh, the Chief of the General Staff of Armed Forces Mikhail Moiseyev, Chief of Staff Valery Boldin and several other employees of the highest-level of importance.

One can say with certainty that it was a unique session in the world history of the oil industry when the operational matters of creating a joint venture were discussed at such level.

The date of the session is particularly interesting – it took place on the eve of Mikhail Gorbachev’s historic vacation from which the President of the USSR returned to a different country and in a different capacity.

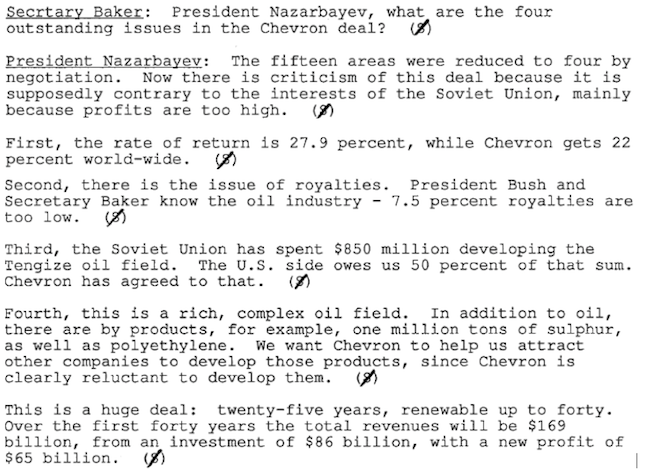

At the session, Nursultan Nazarbayev acted as the main reporter. Curiously, the discussion started with Baker’s direct question: “what are the four outstanding issues in the Chevron deal?”. Nazarbayev responded that there had been as many as 15 issues but, as a result of the complex negotiations, only four remained. All of them were financial.

First, in Nazarbayev’s opinion, Chevron’s rate of return in the new joint venture was excessively high (27.9% against 22% worldwide). We will remark that the rate of return has always been and remains quite impressive. Especially considering that it became an important precedent for the other negotiations and decisions.

“Second, said Nazarbayev, there is the issue of royalties. President Bush and Secretary Baker know the oil industry – 7.5% royalties are too low”. (One can envision Nursultan Nazarbayev looking at the American colleagues with reproof).

The third issue was the return of US $425 mln – 50% of the amount the USSR had already spend on Tengiz’s development.

The fourth issue had to do with the aforementioned sulphur. Nazarbayev believed that Chevron did not want to deal with it and insisted that the company attracted other partners capable of using the sulphur as operating supply.

The Dealmaker

Summing up his opinions, Nursultan Nazarbayev, once again, told the participants about the scale of the future business – a 25-year contract with the right to prolongate it for another 40 years. During this period, the anticipated investments were to constitute about US $86 bln, revenues – 169 bln, profit – 65 bln.

Noting of this kind had existed in the history of the USSR’s foreign economic relations. However, Gorbachev’s remark sounded somewhat mundane: “Generally speaking, the negotiations are progressing “normally”. There is nothing unsurpassable”. For the Soviet leader, as we know, it had always been a matter of importance that “the processes were progressing”.

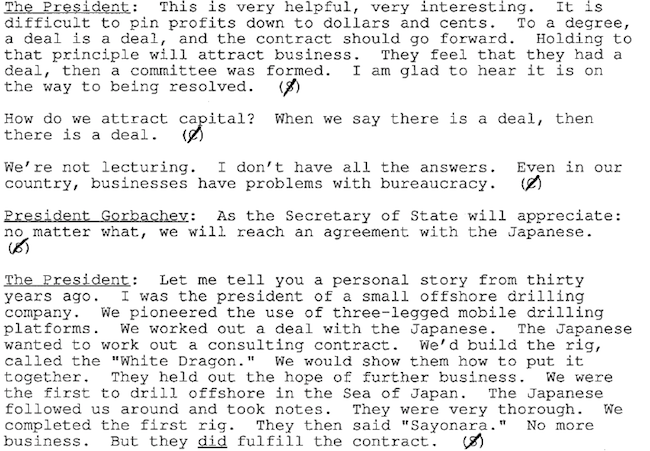

Then, George Bush who knew the oil business firsthand joined in the discussion. He reminded that, in a contract, the numbers are not as important as the signers’ commitment to move forward.

Then the President of the United States recalled the case from his own rich business-biography of how he, as the president of a small drilling company, became a victim of the strategy of a Japanese company that invited his firm to start the business in the Sea of Japan, held out the hope of further business and then, having received the necessary knowledge and expertise, said “Sayonara” (“Good buy”). The main lesson of the story, George Bush said, was that “they did fulfill the contract”.

There is no doubt that Chevron’s management, in contrast with Bush’s small firm, possessed many more instruments not to allow anyone to say “Sayonara” to them unless the company decided to say it first.

Then Nazarbayev joined the conversation again reminding the participants about his personal input in the creation of the joint venture. “I put the deal back on the table after people were afraid it would collapse”, said he.

According to Nazarbayev’s estimates, it should have taken from 40 to 60 days to finish up the contract. In other words, it was supposed to have been signed as early as the fall of 1991. It is possible that the regret about the missed opportunities that resulted from the tearing up of the contract precluded Nazarbayev from exiting the USSR in 1991 up to the very last moment since the Kazakhstan/Chevron agreement was signed only in 1993 and it is now difficult to compare its terms with the Soviet contract.

At the discussion, George Bush seemed the indisputable top dog. And not only from the political standpoint. He understood better than anyone what it was like to conduct the oil business in such complex natural environment. Nonetheless, his remark that this is “a wonderful example of partnership” that would “stimulate other deals” (saying this, the President stipulated that he was “not carrying water for Chevron”) looked like a serious political backing for the corporation given on such a serious political level.

Then the discussion moved on to the political matters and ended up with the very notable and insistent invitations to visit Kazakhstan – to hunt and to rest. The Americans joked it away not showing an explicit desire to head out to the heart of Eurasia.

An Epilogue for Chevron

Three weeks after the meeting, the country experienced the events that put an end not only to the Soviet Union but also to the big plans of Chevron.

Undoubtedly, had the deal been completed successfully, Chevron would have become not just the leader of the Soviet oil market but a true architect and trendsetter. Given the USSR’s total deficit of the money, technologies and expertise, it would have set the rules of the game in the field of oil exploration and extraction. And the history of the private oil entrepreneurship in Russia would have developed very differently. But the deal went sour.

The signing of the agreement on founding Tengizchevroil joint venture. On the photo, former CEO of Cnevron Corp. Kenneth Derr and President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev

In the Kazakh version of Tengiz, the company plays an important but not the exclusive role. 25% of Tengizchevroil’s shares belong to ExxonMobil, an American multinational oil and gas corporation and Rockefeller’s trust’s main heir (another 5% belong to Lukarko, Lukoil’s affiliated company). But, in the Russian oil sector, the company has no serious projects. They could have appeared in the summer of 2003 when the company was negotiating with Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Roman Abramovich on the purchasing of UKOS and Sibneft. But these plans ended with a political disaster for the Russian participants of the deal.