After our last year publication on the problems of Kashagan, we learned that it was taken quite hard in certain political circles (see The Grand “Sawcut” of Kashagan). At that moment, it was not clear as to why, so we decided that the matter lied in the large-scale problems of Kashagan that is the biggest oilfield beyond the OPEC limits. Nonetheless, as it turned out, something else was at play here.

The reasons for such pained reaction to our publication were of a more specific nature. Obviously, already at that point, the Kazakhstan authorities were anxious whether they would be able to keep Kashagan in the hands of the state. Now these anxieties have become widely known.

The thing is that the assets arrested by the Amsterdam court in connections with the claims filed by the family of a Moldovan entrepreneur Anatol Stati included the shares of Dutch KNG Kashagan B.V that amounted to $5.2 bln. However, the price of these shares fades in comparison to their significance. We are talking about the 17% share that the company owns in the consortium developing Kazakhtsan’s biggest oilfield – Kashagan. Recently, it has become known that Stati asked court enforcement officers to sell the stock if Astana refuses to pay $500 mln under the arbitration court decision.

In other words, if the experts do not have doubts as to the future of the reserve assets (the frozen resources of the National Fund of Kazakhstan) since everyone believes that they will, eventually, be unfrozen, then, in regard to Kashagan, such unanimity is to be desired.

The History of the Business

Anatol Stati started doing business in Central Asia in the mid-1990s. In 1995, the Moldovan entrepreneur invested $100 mln in the oil and gas projects in Turkmenistan. At the same time, his company called Ascom (Ascom Group) was implementing projects in Sudan and Iraq. In 1999, Anatol Stati and his team, trough the Tristan Oil offshore company, bought the shares of two Kazakhstan companies, Tolkynneftegaz and Kazpolmunay, that were developing the Barankol and Tolkyn oil and natural gas fields.

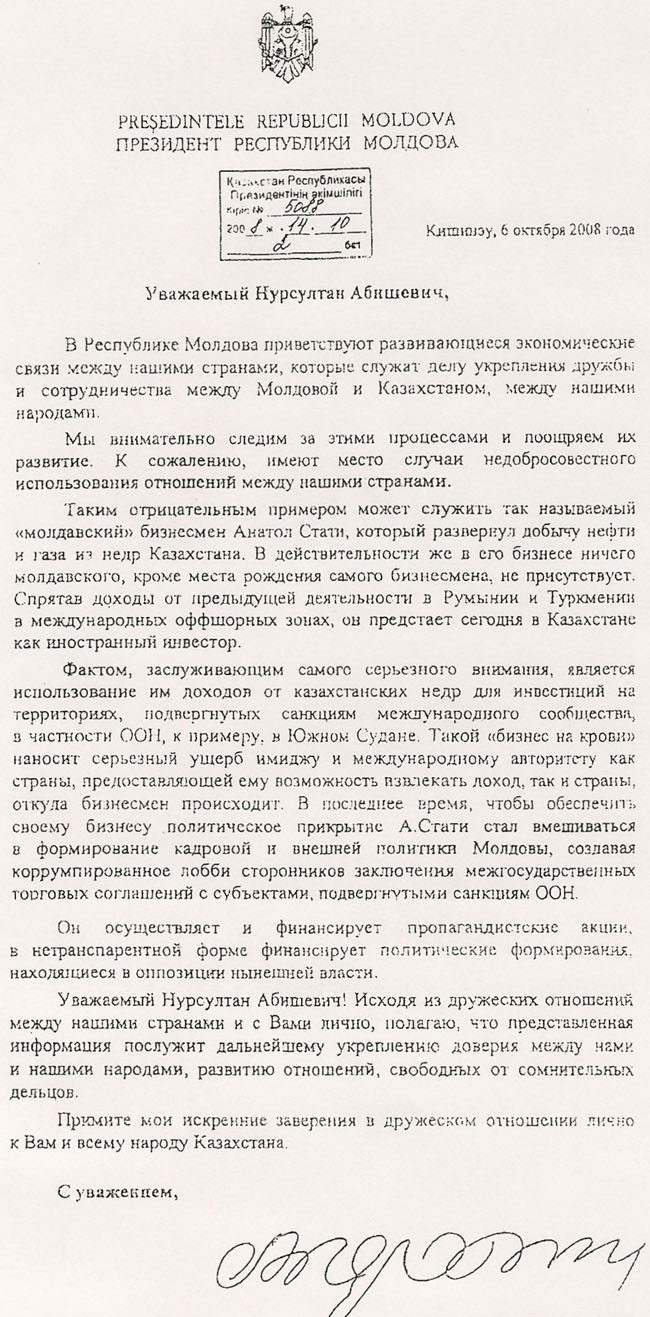

Stati began to experience problems with his Kazakhstan business in October 2008 after Moldovan President Vladimir Voronin sent a personal note to Nursultan Nazarbayev. Voronin was preparing for the parliamentary elections and wanted to strip his competitors off the financial support. In his note, Voronin accused Stati not only of interfering with the Moldovan affairs but also of supporting the international terrorism (which, at the time, was still fashionable and topical). In reality, however, it looks like Voronin and his circle were not fighting the terrorism and not even Stati bit Moldovan ex-President Petr Luchinsky who had tight political and business connections with the latter.

This note, back in the day, was published by the Respublika analytical Internet-portal.

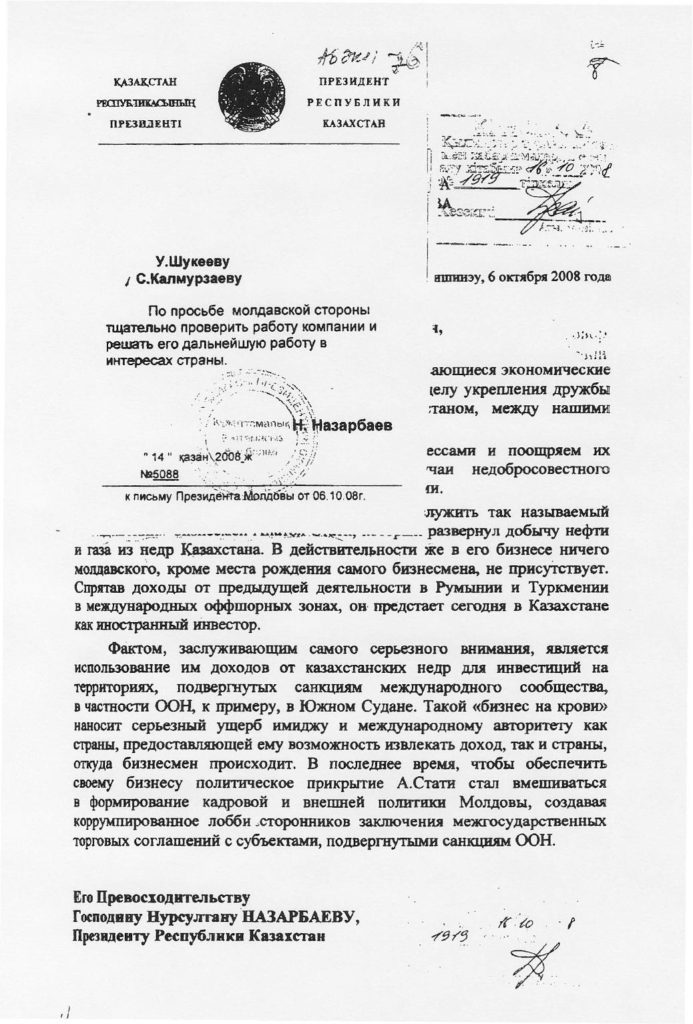

Nazarbayev’s resolution on the note was published in the Respublika as well.

Vladimir Plakhotnyuk who, at the time, was called “Voronin’s behind-the-scenes architect” was advocating the matter. Fast-forwarding, we note that Kazakhstan’s support helped neither Voronin nor Plakhotnyuk who was counting on assuming the chair of Moldova’s Prime Minister. In the spring of 2009, riots sprang in the streets of Kishinev and, on September 11, 2009, Voronin stepped down from the presidency. Plakhotnyuk was forced to start his own political project.

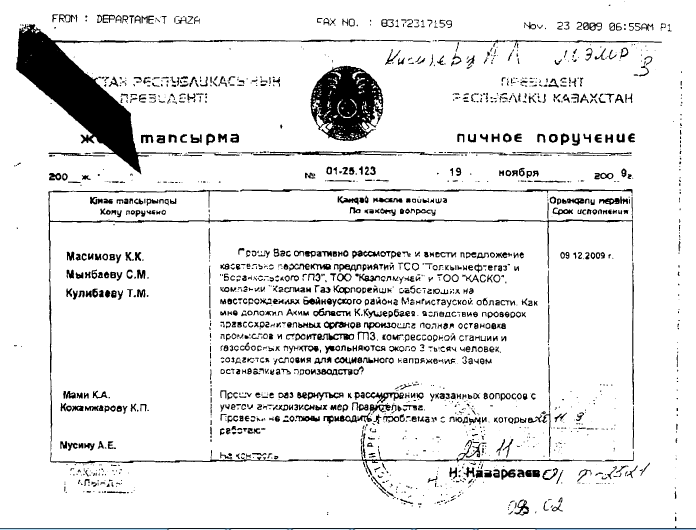

The start of the Kishinev riots coincided with the beginning of the operation against Stati in Kazakhstan. However, the attack of the Kazakhstan siloviks was nothing but a usual special op. In the spring of 2009, they arrested Stati’s trusted representative in Kazakhstan Sergey Kornegrutsu while the financial police were making searches in the Tolkynneftegaz and Kazpolmunay offices. In the summer 2009, the Kazakhstan tax police demanded that Ascom Group paid $1 bln. To do so, the siloviks had to really push the boat out and requalify the infrastructural pipelines belonging to Tolkynneftegaz and Kazpolmunay as the “major pipelines”. This enabled them to accuse the company of conducting unlawful business activities exploiting these very “major pipelines”.

In October 2009, Kornegrutsu was sentenced to four years in prison with the property seizure, and, already in February 2010, Anatol Stati’s representatives announced the sale of the Kazakhstan business to some investors acting in “Kazakhstan’s interests”. However, in July 2010, the government decided they knew better who would be best to act in “Kazakhstan’s interests” and transferred the fields to KazMunayGaz for trust management.

After that, the events started to unfold in the unfortunate for Akorda manner. First, in October 2010, Sergey Kornegrutsa fled from the penal colony settlement in Atyrau. Shortly before that, he had been transferred there from the standard regime penal colony. The fact that all this was a part of a previously worked-out plan became obvious than the colony administration tried to hide the prisoner’s escape by passing him off as someone else. When this failed, the colony management found itself under investigation.

At the same time, Ascom filed a suit against the Kazakhstan government to the Stockholm arbitration court. The cause lied in the company’s default on the Eurobonds issued to finance the projects in Kazakhstan, the foundation – in the accusation of violating the conditions of Energy Charter – the international rulebook for the energy industry signed and ratified by Kazakhstan. Stati estimated his losses in the sum of about $1.6 bln (about a billion of which consisted of lost investments).

The Trial History

On September 23, 2010, the Stockholm arbitration court admitted to examination the claim filed by Anatol Stati against the Kazakhstan government demanding the latter to pay him $1 bln. On December 19, 2013, the “troika” of judges (Professor Karl-Heinz Bockstiegel, Professor Sergey Lebedev, and Mr David R Haigh QC) reached a verdict. The Kazakhstan government was to pay the Moldovan family $500 mln.

In 2014, Stati’s representatives started the legal procedure of implementing the Stockholm’s decision in the US courts. They needed it to ensure the compulsory nature of the payment the amount of which was determined in Stockholm since the Kazakhstan government was refusing to pay and was not accepting defeat. The government’s legal representatives used three arguments – the absence of the current agreement on arbitration procedures, the wrongful choice of the arbitration court judges, and the other procedural violations.

A true legal war began. Kazakhstan accused Stati of fraud carried out when presenting the documents to the court. The Borankol gas processing plant the construction of which had been started in 2005 by the Stati company was at the center of the legal debates. The construction of the plant was practically finished, but, understanding all the legal risks, KazMunayGaz decided not to complete the project. It was explained that the decision was made of the personal order of the president of Kazakhstan.

One can only guess what kind of security the facility had and what its employees had been doing all these years, but the eyewitnesses from Mangistau say that the practically finished construction was plundered and is now nothing more than a colorful decoration for a techno thriller film set. This fact, on the other hand, enables Kazakhstan’s advocates to state that this was not a plant but a failed project that must, therefore, be valued at the price of the metal junk.

Stati’s representatives believe that they invested $245 mln in the construction. According to the state, the price for the equipment shipped to the plant was set too high since it was purchased through a straw company controlled by Stati. As a result, according to the government, the equipment bought for $124 mln, in reality, cost 31 mln euros.

Apart from that, it is unclear where another part of the equipment in the amount of $72 mln went. According to Stati’s lawyers, it was delivered to the plant but not yet installed. The state’s representatives say they did not find the equipment and the plant simply did not have enough space to keep it. They also believe that the demand to pay $44 mln to Perkwood for providing construction management services is unreasonable.

Stati, however, has his own line of argumentation. To prove his point, he supplied the price offers to purchase the plant made by different parties. The offer made by KazMunayGaz’ affiliated company looks particularly interesting among the others on the list. In September 2008, the company’s representatives offered to pay $199 mln for the “failed project” and the “metal junk storage”. The state’s plans to complete the construction of the plant already in 2012 speaks about the seriousness of these intentions. The plant was also mentioned in the official lists of the Mangistau investment projects where they also gave the final price of the project – $315 mln.

There is nothing surprising in the fact that the US court that investigated the fraud accusations did not take them seriously. The surprise lies in the perseverance with which the Kazakhstan authorities had been insisting on them. And they still are. The legal debate is to pick up again in the fall.

The Strategic Prospects

Regardless of the debate prospects, it had long been carried out at a much more serious level and possesses an obviously strategic nature for Kazakhstan. And not just for Kazakhstan. First and foremost, due to the fact that the restrictive measures included the arrest of the assets belonging to the country’s National Fund.

The major role in this event was played by Bank of New York Mellon that acted as a depositary for the National Fund of Kazakhstan. The bank froze the assets in the amount of about $22 bln. The decision followed the Belgian court’s verdict to freeze the Fund’s savings portfolio (in the same amount). Half of this portfolio consisted on the US Treasury bonds – the debt commitments of the country’s federal government. For the whole world, this is the safest type of assets that, de-facto, perform the role of monetary resources for large financial institutes. But, for Kazakhstan, this is no longer an option.

The accounts in the Swedish SEB-Bank depository where they kept the shares of the 33 Swedish state companies (including Volvo, Skanska, Electrolux, Nordea) that belonged to Kazakhstan had been frozen following a separate court’s decision. The assets in the Eurasian Natural Resource Corporation had been frozen in Luxemburg.

De-facto, the debate as to the price of the gas-processing plant in Mangistau (in the amount of several hundred million US dollars) had led to the international financial war against Kazakhstan. The main prize in it, however, may turn out to be Kazakhstan’s share of Kashagan. In September 2017, the Amsterdam court froze the shares of Dutch KMG Kashagan B.V. that was founded in 2005 by KazMunayGaz with the goal to manage Kazakhstan’s participation share in the North Caspian Sea Production Sharing Agreement. It owns 16.88% shares in this project.

In reality, the situation with the management of this share is much more complicated. Apart from the Dutch company, certain limited liability partnership PSA is participating in managing the Kazakhstan share of Kashagan. The company was founded in June 2010 by KazMunayGaz and then immediately transferred to the Ministry of Oil and Gas for trust management. Through it, based on the letters of attorney given by the Ministry of Energy, PSA acted as the authorized agent in the product sharing according to the North Caspian and Karachaganak Production Sharing Agreement. From June 20, 2016, PSA has been performing the same functions based on special government order #355.

At the same time, KazMunayGaz is transferring its properties to the Dutch company of the Samruk-Kazyna Fund. And these processes are affecting the sales of the not yet extracted Kashagan oil to the global international oil-traders (therefore, if the obligations will not be fulfilled, this share is likely to become their property).

Not being an insider, it is hard to understand the perplexities of this management system. However, it is obvious that the Kashagan story is not as simple as they are trying to paint it. And it is not yet possible to say who the owner of Kashagan will be in a couple of years. It is especially interesting to note that the hoo-ha with Kashagan developed simultaneously with the escalation of the legal conflict surrounding the Mangistau gas plant. These stories are likely connected not just chronologically and the relationships between the participants and the goals of the ongoing financial war are much more complicated than they may seem.