Analyzing Kazakhstan’s standing in the Worldwide Governance Indicators rating has allowed us to reach the conclusion that the customary post-Soviet juxtaposition between social order and the level of political freedom is now tottering. The high ratings are ensured by the technological methods and, in our opinion, present an intricate version of the «cargo-cult» — creating a desired form that has nothing to do with the content.

The Worldwide Governance Indicators international project is realized by a World Bank team. Starting from 1996, the experts assess the quality of the power and the governance in more than 200 countries on a regular basis.

The purpose of the project is to evaluate the efficiency of the institutes and the practices of state governance. In other words, the World Bank analysts assess the processes of electing, monitoring and changing the government in the countries represented in the rating, evaluates the abilities of the governments to develop and carry out balanced policies, the citizens’ attitude towards these institutes.

The complex indicators are developed in the basis of more than 400 primary indicators — the statistical, polling and expert assessments that are gathered from 32 types of sources.

The sources include:

- households and firms’ examinations (9 sources);

- commercial sources of business-information (4 sources);

- non-governmental organizations (11 sources)

- civil sector organizations (8 sources).

The results are tied together in the aggregate indicators according to the six generic characteristics of state governance:

- freedom of speech and accountability of the government;

- efficiency of the governmental work;

- quality of regulation;

- rule of law;

- control of corruption.

As we can see, state governance, according to the authors of the project, does not boil down to the governmental functions. The efficiency of the executive branch of the government is only one of the six indicators of the governance system. Essentially, the other five reflect the efficiency of the other two branches of power — the legislative power and the judicial power. The three branches of state power are connected via the system of social interactions. And, as the practices of the past and current centuries show, this system may find itself under a rather effective control of the ruling clans (or one of them).

Understandably, we have chosen to compare Kazakhstan with the other states of the former USSR but did not include the Baltic counties that are now part of the EU and Turkmenistan that is dwelling in its own totalitarian space in the analysis.

Each country’s standing in the WGI project is given in the form of a rank. The estimates vary from 0 (the lowest level) to 100 (the highest level). Each country’s rank reflects the percentage of the countries in which the quality of the governance is lower than in this state. The higher the rating, the better the quality of governance is. World Bank does not present a unified rank based on all the six macro-characteristics since it would not have an analytical significance (unless, of course, we count attracting the attention of the mass audience).

Freedom of speech and accountability of the government

Freedom of speech and accountability of the government is the indicator that reflects the perception of to what extent a country’s citizens can participate in electing the government as well as the freedom of expression, assembly and the media.

In terms of this indicator, Kazakhstan is quite predictably placed at the rear of the world ranking chart. Only 14-15% of the states analyzed in the project have a lower level of freedom of speech and governmental accountability than Kazakhstan.

Not surprisingly, among the «losers», Belarus, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (Turkmenistan is not included in our analysis) outrun Kazakhstan, and confidently so. On the other hand, the ratings of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine are of a completely different «political universe». These countries constitute a part of the 60% of the free countries (about 40% of the states have it worse than they do).

The ratings of Armenia and Kyrgyzstan are significantly higher than that of Kazakhstan; on the other hand, Russia’s rating has grown closer to the ratings of Armenia and Kyrgyzstan (in 2007, the gap was more significant).

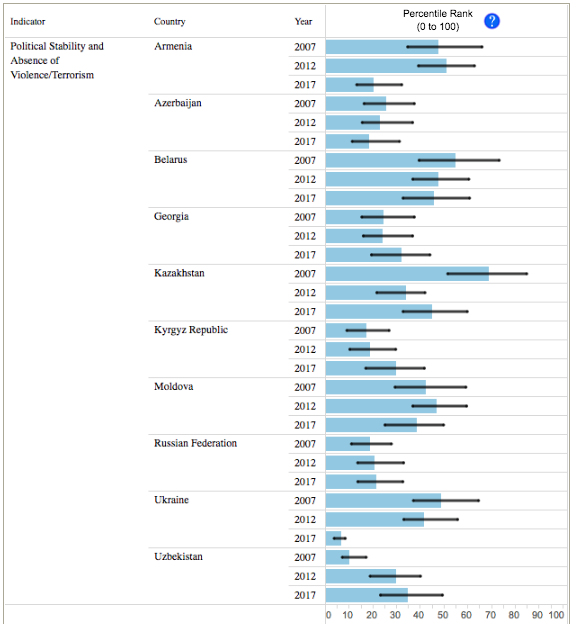

Political stability and the absence of violence/terrorism

This indicator reflects the perception of the possibility of destabilizing the government or of its removal via the unconstitutional means including the terrorist threat.

Unfortunately, the level of this indicator in the countries analyzed is in almost complete opposition to the level of political freedom. It is clear that the outsiders of the freedom rating usually turn out to be the leaders of the political stability rating.

And this is the tragedy of the post-Soviet space. It lies in the inability to build a stable political system. More often than not, freedom of speech means freedom of revolutions. But, if in the 19th century France this scenario would have no significant effect on the country’s economic growth and France remained among the leaders in terms of all the other indicators at any moment of its complicated political history, now carrying out such a scenario is non-feasible.

In this «post-Soviet» rule, there is one very important (and universal) pattern. If we look at the dynamics of the political stability rating in Belarus and Kazakhstan, we will find an alarming tendency for this indicator to grow lower.

This tendency can be perceived as «alarming» because it essentially follows the Soviet Union’s trajectory. The USSR, albeit as stable as it gets, was slowly decaying until it collapsed.

In this light, it is interesting to assess the ratings ratio of Russia that is not among the leaders neither in terms of stability nor freedom. A special case.

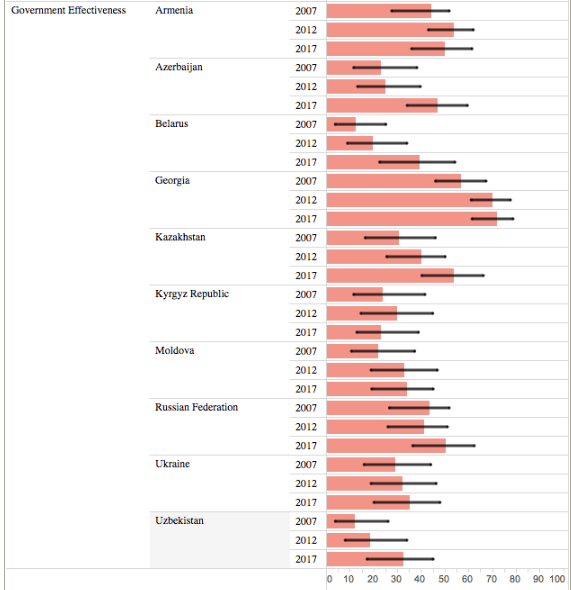

Efficiency of the government work

This indicator reflects the citizens’ perception of the quality of the state services, the level of their independence from political pressure, the quality of developing and implementing policies as well as the level of trust to the political decisions of the government.

There is nothing strange or paradoxical in this rating. In essence, it reflects the general evolutionary pattern in the post-Soviet space and is either going up or is stable; there is no negative dynamics. In other words, the indicators collected by the experts do not show the degradation of the state power quality.

Nonetheless, this indicator it too complex for a simple assessment. The modern information technologies can, with relatively low investments, switch a lion share of the routine state work to the service mode. And this radically changes the citizens’ perception of the state’s functions even though little has changed from the standpoint of the government work efficiency. For example, it is a well-known fact that the automatization level of the state services in the US leaves a lot to be desired. Nonetheless, this fact can hardly be used as an argument for its general inefficiency.

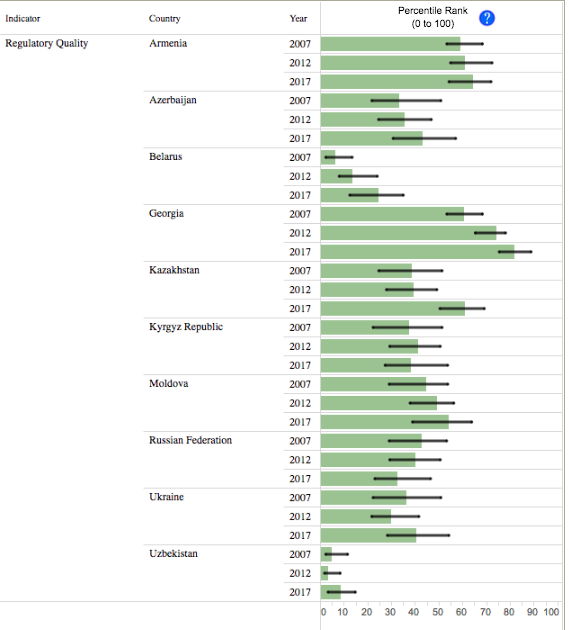

Quality of regulation

This indicator reflects the perception of the government’s ability to formulate and carry out rational policies and rules that help the private sector’s development.

Here, there is also not too many surprises. But Kazakhstan in the only exception. In recent years, the country has made a serious leap forward in terms of this indicator. As a result, the country has moved up to the top of the world’ best-regulated economies.

There can be different explanations for this leap. The most feasible one is a formal one. To advance in this rating, it is enough to pass certain laws and implement certain procedures. The effect these changes have on actual business may not even be reflected by the rating. Of course, this is just a conjecture.

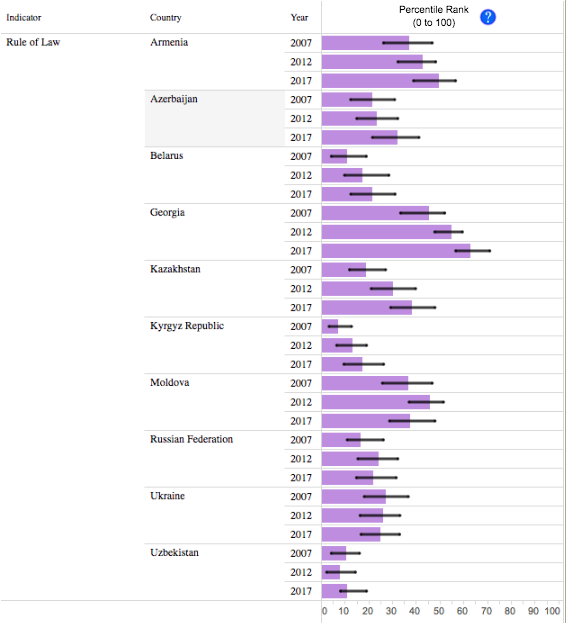

Rule of law

This indicator reflects the perception of how people and organizations adhere to the principles of the social pact — the quality of contract execution, property rights protection, police and court work as well as the level of crime and violence.

In this rating, Kazakhstan also holds a rather high standing which goes against the established perception of how the law-enforcement agencies work in this country.

Of course, in this light, we may recall the Soviet history in which the law had undoubtedly determined the order of life. However, in reality, the law had always been subordinated to the political will and advisability. So, as a result, it was the proverbial telephone receiver and not the judge’s robe that decided the fates of the people.

On the other hand, this scenario is contradicted by the Belarus example. Stereotypically, this country is perceived as a territory of «social order». However, in the WGI rating, it occupies lower positions (albeit the indicator is developing positively). We can only assume that no law, even as a façade, exists in Belarus.

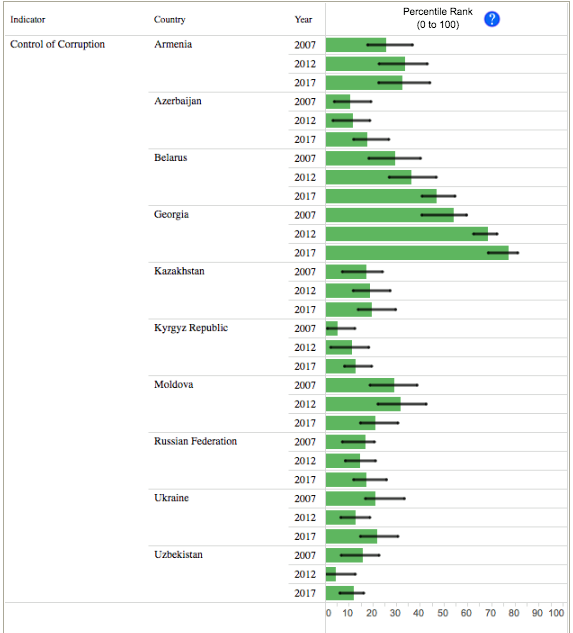

Corruption control

This indicator reflects the perception of to what extent the state power is being used for personal gain as well as how widespread corruption is and whether the state power can be «seized» by elite groups and private interests.

Once again, the Belarus example is striking vis-à-vis this rating. Apparently, Belarus is actively growing as a corruption fighter, but it looks like the fight is being performed only by the uncompromising anti-corruption champion Alexander Lukashenko.

In this light, the Soviet history of Stalin’s times is also relevant. The fight against corruption did not stop for a second, the camps were overfilled with prisoners convicted for stealing state property. At the same time, it was supposed to be the country where «no one would dare to steal anything».

The Georgian case is peculiar. The country has an extremely high standing vis-à-vis this indicator. Most likely, it reflects the people’s perception of the successes of the anti-corruption war.

The low standing of Kazakhstan (as well as of the other post-Soviet states), in our opinion, reflect the real state of affairs. The flashes of the authoritarian enthusiasm to eliminate corruption can fool no one since the majority of the people lives in accordance with these corruption rules. How this system can be changed in the future is a very big question.