About one third of the Kazakhstan economy lies in the shadow. In this regard, the country occupies the 107th place on the list of 158 countries published on the IMF site. Note that the “shadow” part does not include the “usual” criminal economy and the household work. If they were included, the share of the shadow economy in Kazakhstan could easily increase twice.

The shadow economy is known under a variety of different names – grey economy, hidden economy, “cash economy”. Everyone understands that this economy is measured by trillions of dollars. First off, however, it would be a good idea to estimate its economic component.

Leandro Medina and Friedrich Schneider, the authors of the article called Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years? published on the IMF website try to separate the sheep from the goats. It is an academic article but, since it was published on the IMF site, everyone cites it as the organization’s estimates which, in essence, does not change the core of the matter because it is not an economic but a statistical publication. Using a series of statistical exercises, the authors try to exclude the earnings from the criminal sphere and the household work from their estimates. Both the first and the second sectors live by their own laws and rules and their connection to the outside world is but circumstantial. However, the usual analysis of the shadow economy based on the resource consumption and the national accounts inevitably cover them which does not clarify but rather hide the actual state of affairs behind yet another curtain.

The shadow economy as analyzed by the authors includes the types of the economic activity that are hidden from the official authorities due to the financial, regulatory, and institutional reasons. The first group of the reasons has to do with tax evasion and the avoidance of the social security payments. The regulatory group has to do with the attempts to avoid the bureaucratic and regulatory pressure. The institutional group includes the corruption factors as well as the quality of the political institutions and the weakness of the legislative environment.

The analysis is based on the assumption that the people do it consciously, being aware of their actions and making their decisions after considering all the pros and cons. This approach allows to establish a system of the cause-and-effect relationships. Violating the law has a negative relationship with the probability of being caught and the scale of the punishment. But it has a positive relationship with the alternative costs the person will have to pay if they remain in the formal economic field. The factor of the effectiveness of the law-enforcement system also plays against the possibilities to work in the “shadow”.

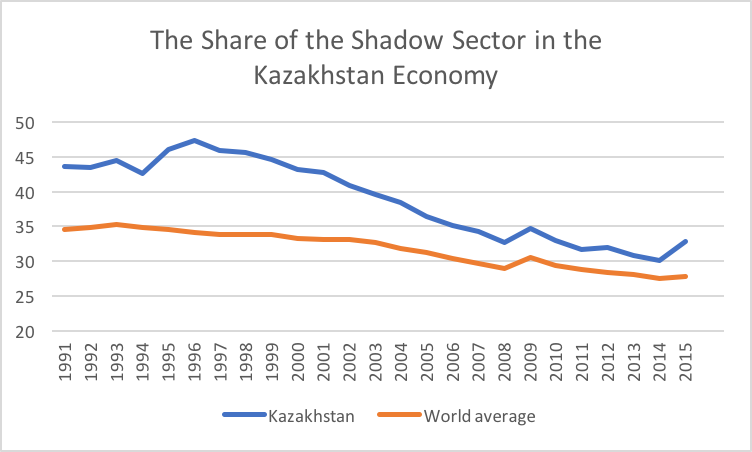

On the whole, from the beginning of the 1990s to the year 2015 (the period analyzed by the authors of the IMF article), the trend had obviously been to “clean” the economy. The share of the shadow economy had decreased from 34.8% to 28%. This trend, however, always gets disrupted in times of crises. Clearly, the crises become the reason for the entrepreneurs to reconsider their relationships both with the state and the society.

In Kazakhstan, the share of the shadow economy exceeds the average indicator among the 158 countries presented in the publication. (By the way, the first positions on the list are predictably occupied by Switzerland, the USA, Germany, and the Netherlands; the last ones – by Zimbabwe, Haiti, and (unexpectedly) Georgia). But if, in the 1990s, the gap between Kazakhstan and the average indicator seemed impassable (reaching 13% in 1996), then the situation had improved, and the gap had become smaller reaching the critical minimum of 2.62% in 2014.

The reduction of the shadow sector in Kazakhstan had been happening simultaneously with the decrease of the world average indicator, albeit faster. According to the authors of the article, the share of the shadow economy in the Kazakhstan GDP structure had decreased by one third during the observation period. But, in 2015, the gap began to grow again. It means that the size of the shadow economy does not change and its share only decreases as a result of the growth of all the parts of the economy. Therefore, it suggests a more stable nature of the shadow economy: during the economic downfall, it keeps its size becoming a more important factor of the national economic system.

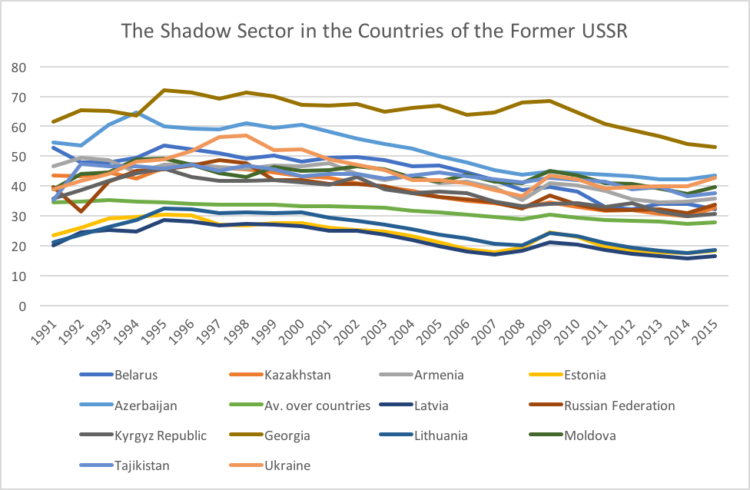

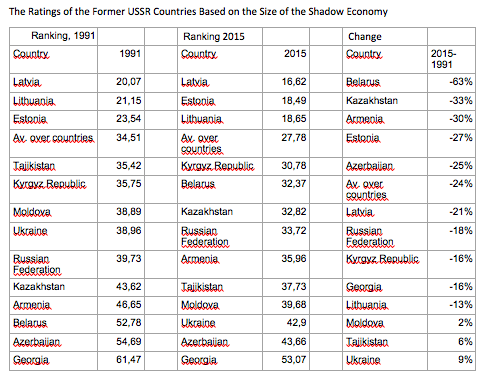

In 1991, according to the authors’ estimates, Kazakhstan was the last one on the list of the five former USSR republics compiled based on the size of their shadow economies. Georgia was the absolute leader, then (by a significant margin) followed the other two Transcaucasian republics – Azerbaijan and Armenia. In general, it reflected the balance of the economic forces in these republics during the Soviet times. The fact that Belarus and Kazakhstan made to the list of the five leaders was much more surprising.

In the next decades, the share of the shadow economy in both countries was decreasing faster than in the rest of them. As a result, according to the 2015 data, both states left the group of the shadow economy leaders becoming some of the most transparent economies of the former USSR (according to the authors of the research). It is possible that, in Kazakhstan, the economy “cleaning” was a result of the economic transformation of the country marked by the growth of the resource sectors due to the arrival of the large transnational corporations. Even if these corporations are hiding something, they do it on the professional level and their shadow operations are unlikely to appear on the national statistical data.

The true grey sector of the Kazakhstan economy consists of households. The number of the “self-employed” allows us to estimate its size. One can only guess by what rules this economy operates: no Western publications on this subject exist and no one in Kazakhstan would take a risk of conducting such a research.

Generally, all the countries of the former USSR (albeit on different levels) show a similar trend: the share of the shadow economy increases in the first half of the 1990s and then decreases taking a break during the crisis of 2008-2009.

The same trend is characteristic of the world economy as well. The only exception is Ukraine where the share of the shadow economy increased in 2015 (the last year of the observation period). Clearly, this can be explained by the aftermath of the 2014 crisis.

Source: estimates of the authors of the IMF article