In the 2016 UN annual human development report, Kazakhstan occupies 56th place in terms of its human development index (HDI). It means the country is among the states with a high level of the human development but is inferior to its EEU partners such as Belarus (52nd place) and Russia (49th place) that belong to the group of the countries with a “very high level of the human development”.

Note that HDI is a complex indicator that includes the objectively measured parameters determining the characteristics of the level of life – life expectancy, literacy, education, and income.

The report prepared based on the 2015 data that encompasses 185 UN members is quite educational. However, there is another, even more interesting, report. We are talking about a large-scale research on Kazakhstan alone conducted by Whiteshield Partners at the UN request. The research presents comparative analysis of the country’s regions according to the parameters that characterize their level of the social and economic development.

We offer our reader some fragments of the research that present the most interesting results and conclusions.

The Outcomes of the Independence

Kazakhstan has been remarkably successful in managing its transition since 1991, with GDP per capita rising from US$1,469 in 1998 to nearly US$13,612 in 2013 and an HDI value increasing from 0.690 to 0.788 between 1990 and 2014. Kazakhstan’s HDI value of 0.788 in 2014 places the country in the high human development category and ahead of the average for peers in Europe and Central Asia, at the 56th place out of 188 countries and territories.

However, social and regional disparities have widened. Kazakhstan faces issues with regional variations in poverty, income inequality and environmental degradation. The HDI value falls to 0.694 when it is discounted for inequality.

Kazakhstan is performing relatively well on human development at the national level, but with strong disparities at the regional level

Kazakhstan’s strong overall human development performance over the last fifteen years hides a more uneven performance at the regional level in terms of capabilities, human development and sustainable development.

Methods and Questions

Leveraging the results of two indexes developed by Whiteshield Partners, the Economic Complexity Index and the regional Sustainable Development Goal Challenge Index, the analytical framework adopted in this report considers the following questions:

- What is the current level of capabilities and sustainable development in Kazakhstan at the national and regional level?

- How to explain the different development paths at the regional level?

- Based on these different development paths, what policies are needed to foster more balanced and sustainable development for all of Kazakhstan’s regions?

Sustainable Development Goal Challenge Index (SDGCI)

To address the existing regional challenges and build long-term comparative advantages, policy makers in Kazakhstan, when preparing the country’s development strategy, need to place a greater emphasis on sustainability and human development at the regional level, to ensure that the benefits of growth impact the widest number of people, leaving no one behind.

The index focuses on 6 SDG dimensions that are most relevant to Kazakhstan’s challenges at both the national and regional level.

- Goal 3: Good health and well-being

- Goal 4: Quality Education

- Goal 5: Gender Equality

- Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities

Each of these SDGs is linked to a number of indicators that have been weighted and standardized.

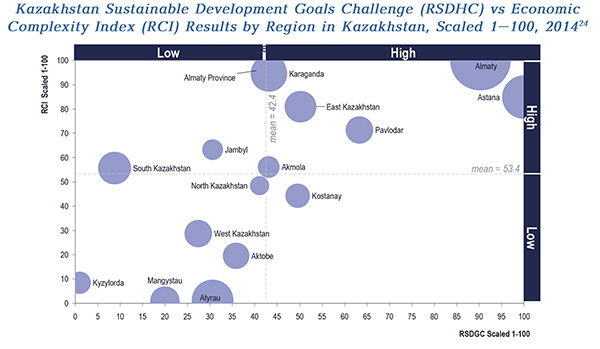

Based on the initial results of the Sustainable Development Challenge Index, four regions lead the country in sustainable development: Astana and Almaty cities, Pavlodar and East Kazakhstan. The regions that lag behind on sustainable development include West Kazakhstan and Mangystau, followed by Kyzylorda and South Kazakhstan.

The Regional Economic Complexity Index (ECI)

To address the existing regional challenges and build long-term comparative advantages, policy makers in Kazakhstan, should not only assess progress on sustainable development but also on capabilities, which ultimately tends to drive sustainable development. The foundation for capabilities, of course, is knowledge, which is also the driver behind economic growth.

This approach uses capabilities, value-chains and territories (or regions) as dimensions for the analysis.

Here are some thought-provoking questions:

- Why are products and sectors of Kazakhstan not moving up the value-chains fast enough vs. peer countries like Turkey?

- Which regions are driving the productive knowledge of Kazakhstan? What is their relative role in contributing to this productive knowledge and how did their role evolve over time?

- Which regions are driving the diversification of the country? Which ones have created new productive knowledge over the reference period of 2003-2015?

- Based on all previous analysis, what vertical and horizontal policies21 can address specific capability gaps in the regions of Kazakhstan and improve their future performance? What is the level of capabilities in Kazakhstan? Kazakhstan is underperforming in terms of capability building compared to its global peers but ahead of its regional peers.

Turkey vs Kazakhstan

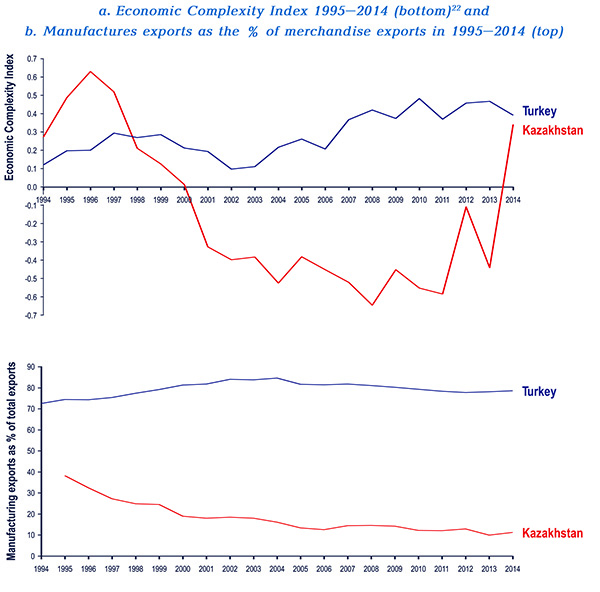

Capabilities are measured by economic complexity, which in turn is closely correlated to manufacturing exports. With additional productive knowledge, a country can expand its production and increase the share of manufacturing in the total merchandise exports. The reverse is also true: increased manufacturing as a share of exports also facilitates knowledge accumulation.

In Kazakhstan, the Economic Complexity Index has been declining since 1996 with several ups and downs over the last five years while the share of merchandise exports has been monotonously decreasing over the reference period. By contrast, Turkey, which started with a lower Economic Complexity Index than Kazakhstan in the 1995, was able to out-perform Kazakhstan both in terms of economic complexity and the share of manufacturing export (except in 2014 were oil price effects distorted Kazakhstan’s performance).

Turkey was selected as a fast-developing regional peer with different export structure and capability development trends. Over a decade, Turkey outperformed Kazakhstan by such indicators as WEF Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) and Economic Complexity Index. Turkey and Kazakhstan were ranked the 51st and the 71st by the GCI in 2005 and the 45th and the 50th in 2014 respectively.

Leaders and Losers

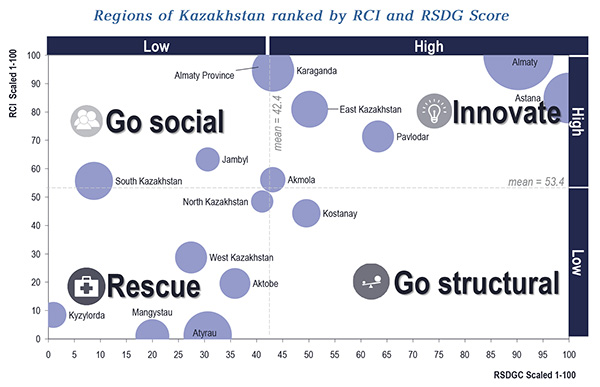

At the regional level, economic complexity is the highest in the administrative cities of Astana and Almaty as well as Karagandy and the Almaty region. It should be noted that the two regions of focus in this report, Mangystau and Kyzylorda, have among lowest level of capabilities in the country (with Mangystau ahead of Kyzylorda).

Only Almaty region and Jambyl went up on both dimensions, none of the regions went up two tiers.

Improving on RSDGC dimension appears more complicated without strong existent positions on Capability dimension. Out of the regions that were both low on RCI and RSDGC dimensions Jambyl and South Kazakhstan have moved up the capability path, Almaty region and East Kazakhstan were already high on Capability dimension and have managed to move up the RSDGC dimension as well; none of the regions that had low RSDGC have managed to improve on it, Kostanai was already high on RSDGC dimension has slightly improved its positions on Capability

dimension. Both Kyzylorda and Mangystau remained stagnant and low on both dimensions.

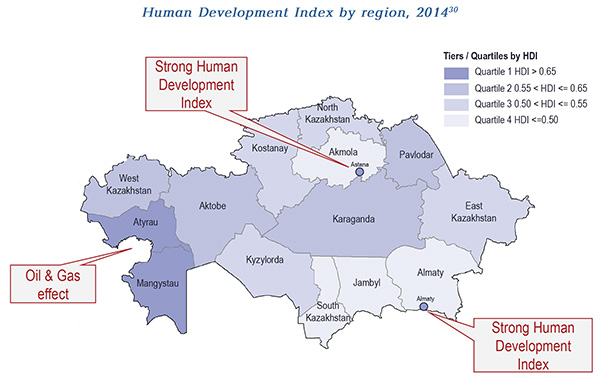

The country’s strong performance in human development can be explained in part by significant Government investment in health and education as well as free and broad access to these public goods. Kazakhstan’s average national performance on human development, however, hides a very uneven performance at the regional level.

The Human Dimension of the Regions

A number of regions are well below the average HDI score for the country, in particular Jambyl, Akmola, South Kazakhstan and the Almaty region, which are the weakest performers, with a score of less than 0.50. Not surprisingly, the administrative cities of Almaty and Astana have the highest HDI scores in the country, followed by the regions of Atyrau and Mangystau, which benefit from oil and gas revenues.

The strong disparities in human development between Kazakhstan’s regions are mirrored by an uneven performance in sustainable development at the regional level. In particular, Kazakhstan faces six sustainable development challenges, all of which are closely related to the SDGs.

These challenges are: (1) High levels of inequality between regions (SDG 10); (2) Uneven development of innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9); (3) Uneven levels of growth, productivity and employment (SDG 8); (4) Regional disparities in terms of health and access to healthcare (SDG 3); (5) Disparities in education levels (SDG 4); (6) Gender inequality (SDG 5).

The first three challenges are primarily at the enterprise level, whereas the next three are related more to individuals.

High Level of Inequality between Regions

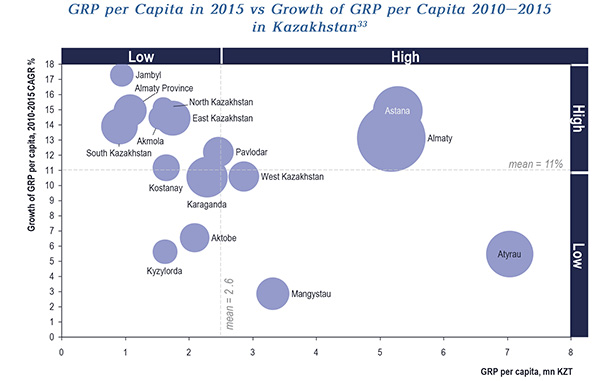

Although GRP per capita has grown rapidly over the last decade in all of Kazakhstan’s regions, the disparities continue to be striking. Consider that Atyrau had more than seven times the GRP per capita of South Kazakhstan in 2015.

Growth rates of regions with established processing sectors, such as Karagandy, East Kazakhstan, Pavlodar, Kostanay etc, although positive, fall behind growth rates of oil extracting regions and cities. It led to decreased contribution of these regions into the country’s GDP.

When measuring inequality in terms of GRP per capita and GRP per capita growth, Kazakhstan has different clusters of regions (see figure below).

The “Laggards” cluster

Includes the regions of Kyzylorda and Aktobe, has both low GDP per capita and relatively low GDP per capita growth. These regions could benefit from both horizontal and vertical policies to bring them closer to the country’s mean income levels. As an industrialised region, Aktobe could focus more on the upgrading and modernisation of its plants and machinery to boost productivity and evolve towards more advanced manufacturing. Kyzylorda should consider diversifying outside of its dependence on commodities, towards other areas such as value added IT services. Another cluster of regions, Jambyl, Almaty Region, North Kazakhstan, South Kazakhstan, and East Kazakhstan, has a much lower GRP per capita (half the mean) but it is growing fast, at 15% per year or more.

The ”Challenger” cluster

May benefit from short-term policies to alleviate poverty – such as wage supplements – but they are already on a trend to reach the national GDP per capita average in a few years.

Atyrau and Mangystau fall into the “Energy based” cluster

R regions that have a high GDP per capita but below average GDP per capita growth. These regions could benefit from vertical policies to boost their level of R&D, innovation and productivity and reach higher levels of growth in wealth creation.

The “winning cluster”

Includes regions or cities that have consistently high GDP per capita and GDP per capita growth. The administrative cities of Astana and Almaty both fall in this category. As the engines of growth and wealth creation in Kazakhstan, the cities of Astana and Almaty could find additional ways to positively impact other regions, namely by establishing commercial linkage programmes with the poorest regions in the country.

Despite positive dynamics of GRP per capita and personal income growth across the regions, it was notably advantageous for bottom 40% (share increase by more than 1 p.p.) only in Astana, Pavlodar, and Almaty region.

Inequality and Growth

the regions in Kazakhstan with the highest level of inequality – Akmola, Karagandy and East Kazakhstan – are also the ones where GDP per capita is growing the fastest. Rapidly growing economies typically generate higher levels of inequality in the short term that can be addressed through targeted policies.

As the regions of Akmola, Karagandy and East Kazakhstan not only have high levels of inequality but are also among the poorest in the country, they could benefit from poverty alleviation measures, such as income supplements for the most needy families. These income supplements could be partly financed at the national level until they become self-sustained through their rapid growth. Further analysis should be conducted to pinpoint the sources of growth in these regions and why it is not trickling down to the broader population.

The lowest level of inequality in Kazakhstan can be found in Mangystau, Kyzylorda, South Kazakhstan and Pavlodar, with a Gini index of less than 0.22. Lessons learned from policies adopted in these regions could be used to benefit other regions with higher levels of inequality.

Uneven Development of Innovations and Infrastructure (SDG 9)

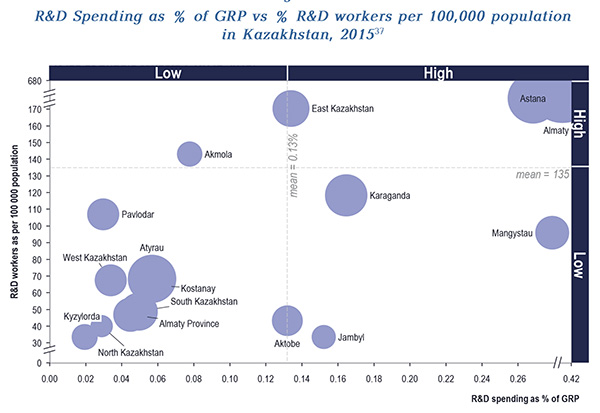

The second challenge, after inequality, is the strong discrepancy between regions in their investment in innovation and infrastructure. The administrative cities of Almaty and Astana stand out not only in terms of their income per capita but also in terms of their investment in innovation, as measured by R&D spending as % of GRP and the number of R&D workers relative to the population (see figure below).

The contrast between Almaty at one end of the spectrum, and the regions of West Kazakhstan, Pavlodar, Kyzylorda, Almaty Region, Atyrau and Kostanay at the other end, is striking. This latter group of regions should consider different ways to invest further in R&D and reduce the gap of up to twenty fold with Almaty.

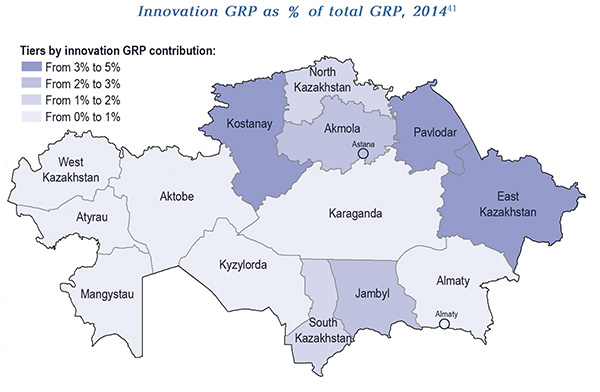

Mangystau also has a relatively high level of R&D spending as % of GRP, in particular for a resource dependent region, but is not clear that this spending is generating results: although exports represent 75% of GRP, only 5% of these exports are non-raw material (see diagram). Moreover, Mangystau is in Kazakhstan’s lowest quartile in terms of innovation GRP as a % of total GRP (see diargam). Mangystau should consider options to better orient its R&D spending so that it translates into innovation.

Uneven Levels of Growth, Productivity and Employment (SDG 8)

The third challenge to sustainable development faced by Kazakhstan’s regions is productivity and employment. Although Kazakhstan’s average unemployment rate of 5% is low by international standards, again there are variations of employment between regions.

The regions with the highest rates of unemployment, such as South Kazakhstan and Mangystau, must strengthen their capabilities, pursue structural reforms and implement active labour market policies. Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) represent an excellent source of employment creation. Although SMEs account for over 90% of enterprises in all of Kazakhstan’s regions, their

contribution to GRP is no more than 20% in all regions except Astana and West Kazakhstan.

Labour productivity is yet another critical dimension of sustainable development in which the regions of Kazakhstan are polarized. The highest levels of labour productivity can be found in the administrative cities of Astana and Almaty. Atyrau and Mangystau stand out as regions with

relatively high productivity but low or even negative productivity growth. These two regions could invest further in skills development through internship programmes, enterprise training, public-private partnerships and linkage programmes between foreign investors and SMEs.

The other regions of Kazakhstan have low but growing labour productivity which can also be better sustained through further investment in training.

Disparities in Levels of Health and Access to Healthcare (SDG 3)

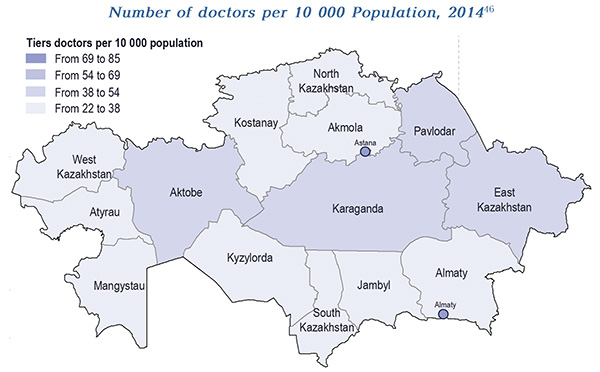

Another important challenge for Kazakhstan’s regions at the individual level is achieving the right levels of health and access to healthcare. Access to healthcare in an advanced industrial nation should be universal and balanced. Yet some regions in the south of the country, notably Mangystau, South Kazakhstan and Almaty, have more limited access to hospital beds compared to their peers in the rest of the country. All the regions except the major cities experience a shortage of physicians: the density of physicians is at least twice lower in regions compared to Astana or Almaty (see diagram).

Substantial disparities in health care are also reflected in “output” indicators, such as child mortality under age 5 per 1000 births. Despite substantial progress during the short period

2010-2014, difference between the worst and the best performing regions is still reaching 2x: 16.45 for Kyzylorda vs. 8.08 for Astana.

To achieve better access to healthcare, regions need to have the appropriate level of infrastructure and incentives for doctors to practice in more remote locations. Mangystau could consider investing a greater part of its receipts from commodity exports into healthcare access. Marketing campaigns and financial incentives should be put in place to attract more doctors to the most remote regions. Moreover, the national Government might consider providing credits to the poorer regions

such as South Kazakhstan or Almaty region to help boost investment in the healthcare infrastructure.

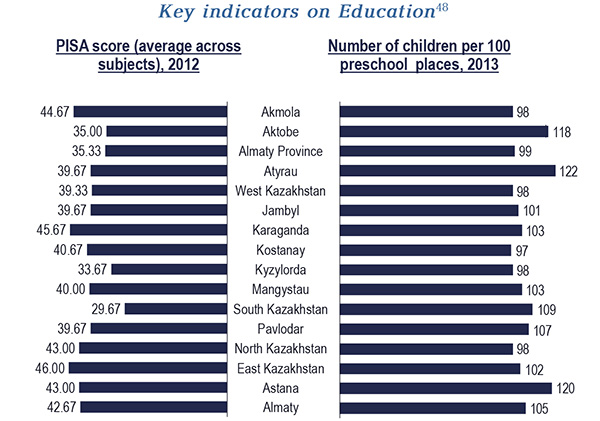

Disparities in Education Levels (SDG 4)

Access to quality education is just as fundamental as healthcare to achieve sustainable development and it should be universal as well as balanced. Access to preschool education also influences women’s participation in labour force, yet 10 regions do not have capacity to accept all children at preschools (see diagram).

Gender Inequality (SDG 5)

Despite important progress made in Kazakhstan to reduce gender gaps in education and employment, there are still notable gaps at the national level and important disparities remain between regions. Consider wage levels: the difference in salary between men and women in regions such as Atyrau and Mangystau is approximately 50%).

Both Atyrau and Mangystau are heavily dependent on commodity extraction, which is typically a male

dominated sector. Wage levels are also inflated by the commodity effect. Mining regions such as Atyrau and Mangystau should put in place to proactive policies to promote the employment of women in the mining sector at comparable wage levels to those of men. Local Government communication campaigns and gender awards can help make firms more responsive to reducing the gender gap. Communication campaigns should also be in place at the high school and university level to encourage more women to pursue careers in engineering and mining.

Strong gender gaps in education can also place women at a disadvantage in holding public offices. Thus Kyzylorda not only has one of the highest gender gaps in literacy rate, it also holds among the lowest proportion of women in public leadership positions compared to other regions (see diagram).

Conclusions and Recommendations

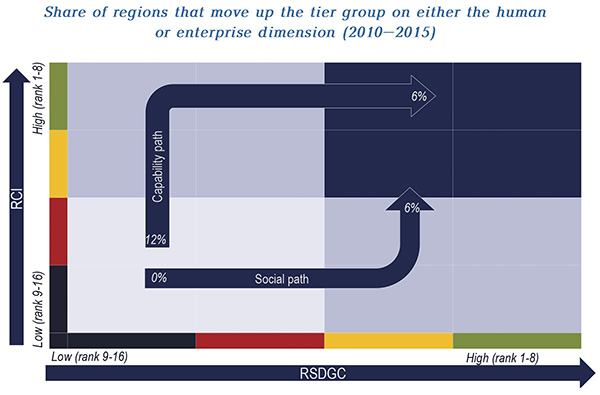

Based on the SDG Index and Capability Index results, it is clear that not all regions are following the same development path. While some regions are more advanced in terms of capabilities, others are ahead on sustainable development. The challenge is to help regions strike a better balance between capabilities and sustainable development within regions while reducing the gaps between regions. Two types of development path were identified – the Capability path and the Sustainable Development path.

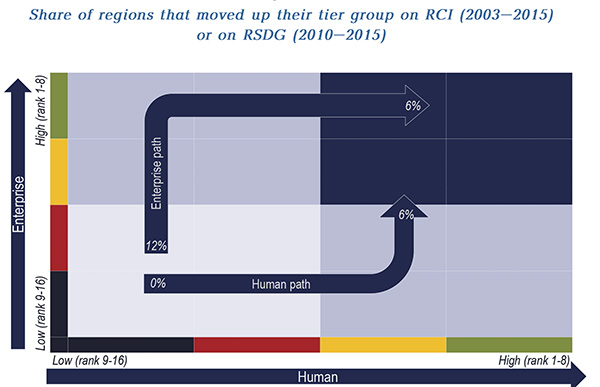

The capability path: most regions in Kazakhstan first follow a capability driven path to development, moving up on the RCI Index and then right on the RSDG Index . These regions have first invested in building the complexity and diversity of their manufacturing and services before turning to improving infrastructure, SME development, employment creation, access health, education, and gender equality. Regions that have followed a capability driven path to development include the Almaty Region, and East Kazakhstan.

The sustainability path (social path): Once minimum capabilities are established, it is also possible for regions to take a sustainability driven path to development. These regions place a greater emphasis early on in investing in people and sustainable enterprises. Kostanai is an example of a region that has followed this path.

Enterprise based development approach prevails initially but should be followed by human development: Regions that follow a sustainability path will typically first focus on enterprise SDGs before turning to human SDGs. The enterprise development approach involves moving upwards and then to the right (see diagram). It is clear that not all regions are following the same development path. While some regions are more advanced in terms of capabilities, others are ahead on sustainable development. Actions to support enterprise SDGs involve investment promotion, the development of techno parks, active labor policies, infrastructure investment and public investment in R&D and innovation.

Aktobe and Mangystau, which were low on both SDG dimensions, started to rise through the enterprise dimension. The Almaty Region, once if was high on the enterprise dimension, shifted over to the human dimension.

Following an initial investment in enterprises, the human development dimension involves investing in people early on before shifting back to enterprises. In graphical terms, the human development approach, adopted by regions such as Kostanay, involves moving to the right on the human dimension before moving up on the enterprise dimension. In the longer run, both capability driven and sustainability driven regions should converge on both the RCI and RSDG Index.

Both development paths have been demonstrated through a 10 years analysis of RECI and SDGI for all regions of Kazakhstan. Within the framework of these two development paths, there are four segments of policy responses that can be adopted by regions:

Both development paths have been demonstrated through a 10 years analysis of RECI and SDGI for all regions of Kazakhstan. Within the framework of these two development paths, there are four segments of policy responses that can be adopted by regions:

“Innovate”: for regions with strong results on both the Economic Complexity Index and SDG Index must focus on R&D support, strengthening linkages between private enterprises and universities, encouraging cross-border R&D collaboration, and attracting FDI that is targeted towards innovation and skills transfer.

“Go Structural”: regions that have a high score on the SDG Index but a much lower one on the Economic Complexity Index must implement measures to upgrade their capabilities through more open competition, FDI-SME linkages, export promotion and public-private partnerships for skills development.

“Go Social”: regions with a high score on the Economic Complexity Index but low score on the SDG Index have not invested sufficiently in human development and sustainability. These regions must focus further on investment in education, healthcare, social security, gender equality and sustainable forms of production and consumption.

“Rescue”: for regions that demonstrate weak results on both the SDG Index and the Economic Complexity Index there is a need for a combination of horizontal and vertical policies to progressively move up the value chain and generate the financing for sustainable development.

FROM THE AUTHOR

Any UN report is, essentially, a diplomatic document that presents the results and conclusion in a way that is supposed to offend no one. Especially if we are talking about the causes and possible consequences of the analyzed phenomena. The report at hand presents a true confirmation of this rule. Its authors are careful to avoid any “uneasy” matters not only in regard to the causes of the regional inequality in Kazakhstan but also of its possible consequences. Essentially, they act in the exact way that the Soviet researches used to act: we investigate, and you read between the lines and draw your own conclusions.

If we are to formulate the essence of the regional processes in Kazakhstan with precision, we may clearly see the disparity of the trajectories, that of the capital and the North-East on the one hand and the rest of the regions on the other. It is particularly important to note that the “rest of the regions” include those with the fast-growing population.

There is a well-known rule: social revolutions happen not because the country has many poor people but because there is a social disparity that is perceived as unfair. But if previously such disparities were, generally, characteristic of the cities where the people were separated only by walls and districts (consider, in Chicago, rich people used to live in the areas that were easy to leave in the case of a social riot), now nothing can stop information from disseminating. The paradox of the modern development lies in the fact that the erosion of the geographic borders achieved through the communication revolution leads to strengthening of the intra-regional tensions.

The authors of the report do not say anything about the North-East dynamics, either. However, it is quite obvious that, in contrast to Turkey, this region, as an economic cluster, had formed within the USSR borders and its integration into Kazakhstan is more a political than an economic matter. Anyway, this may be more of a question than a statement since the subject of the distribution of the traffic flows in the country lies beyond the report framework.

The dynamics of the human capital within the country has also not been defined clearly. According to the report conclusions, it looks like the capitals have become its generators. However, it seems more likely that they rather perform the role of concentrators collecting the human capital from other regions. The later trends indicate the possibility that only the capitals will soon be among the developed regions of the country which, of course, is a highly alarming sign.

The low level of the development of the Western regions seems very indicative. Despite the “golden shower”, they have failed to turn themselves into Texas. Despite all the attempts to build highly advanced development projects in these territories, they were only realized on paper.

This is why, against this background, the authors’ recommendations look particularly amusing. All of them can be reduced to the famous perestroika slogan: “There’s gotta be something that can be done”.