Brazil’s political history is remarkable and multifarious. It has been a “test facility” for all sorts of political governance – a monarchy, a corporate state, an oligarchy, a military dictatorship, and a parliamentary republic.

Brazil used to be a Portuguese colony (gained independence in 1822). Now it is the biggest state in the South America based on its size and population. During its relatively short history, Brazil has tried several different systems of power organization. All of them, however, had one thing in common – regardless of the type of the regime, Brazil changed its rulers quite often.

Corporate State Brazilian Style

Prior to WWII, Brazil was a typical country of its time. In its form, it was a republic, in its essence, it was an authoritarian state. Brazil became a republic after the 1889 military coup d’etat. Then, the ruling junta eradicated all civil rights but had gradually surrendered its power to the civic administration. It was then when the “triangle of scenarios” that had controlled the life of the country during the bigger part of the 20th century (up to mid-1990s) was formed. These scenarios included the populist authoritarianism, the military dictatorship, and the oligarch republic.

The other dimension of Brazil’s political system has to do with the size of the country’s territory and the macro-regions, different in their socio-economic structure. Many emigrants both voluntary (from Europe) and involuntary (from Africa) added an ethnic element to this regional specificity.

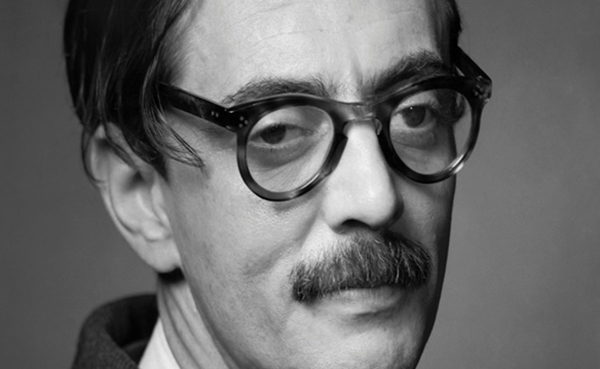

Getulio Vargas was the best-known Brazil’s political leader.

He was a true political long-liver by the Brazilian standards. Vargas’ rule had continued for more than two decades. These decades are divided into two uneven parts, 1930-1945 and 1950-1954 (authoritarian regimes are known for their comebacks).

Getulio Vargas was born on April 19, 1882. He graduated from law school and then received a doctorate degree in jurisprudence. In 1922, he was elected as a member of the Legislative Assembly in Rio Grande do Sul. He served as Minister of Finance under President Washington Luis but resigned to enter the gubernatorial race in his home state. Once elected Governor of Rio Grande do Sul, he became a leading figure in the national opposition.

In 1930, Vargas created Liberal Alliance between the new city bourgeoisie and the landowners who opposed the government. He entered the presidential race as the Alliance candidate but lost the election. He then accused the government of falsifying the results of the vote and started preparing for a military fight.

On October 10, 1030, Vargas and his allies took a train to Rio de Janeiro. Attempting to stop him, the governmental troops blocked the roads and, as a result of this, on October 12-13, armed conflicts with the revolutionaries occurred on the border of Sao Paulo and Parana states.

A major conflict could have happened in Itarare but was prevented by the fall of the government on October 24, 1930. Temporarily, the power went to the junta. A week after that, Vargas arrived in Rio de Janeiro and, on November 3, 1930, at 3 p.m., the junta officially surrendered the power to him. Vargas started to rule Brazil as Interim President.

Historians believe that Vargas’ “true authoritarianism” took place in 1937-1945. During this time, the institutes of the new state (the corporate state whose model was borrowed from Brazil’s former parent country Portugal) had been established.

The scenario of how to hold on to the power, too, was borrowed from the Old World. To be precise, from the Nazis. The president’s people uncovered a “communist plot” that was a roadmap of how to obtain the power. It was a fabrication but, for Vargas, it played the same role as the Reichstag fire did for the Nazis.

On February 27, 1933, the Berlin Fire Department received a message that the Reichstag was on fire. Despite the best efforts of the firefighters, the fire was put out only by 22.30. In the ruins, they found and arrested Marinus van der Lubbe, a former communist. Hitler declared that the fire was started by communists and advised President Paul von Hindenburg to issue Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State that eliminated individual liberty, freedom of assembly, association, speech, and press. It limited privacy of correspondence and inviolability of private property. The Communist Party of Germany was banned from existence. In a matter of days, they arrested about four thousand communists and many leaders of the liberal and socio-democratic groups including the Reichstag deputies.

After the Cohen Plan was uncovered in Brazil, the country declared a state of emergency and Vargas became a dictator.

Vargas’ corporate dictatorship Estado Novo (the New State) had finally materialized in 1937. Vargas was supposed to leave the presidential post in January 1938 in accordance with the 1934 Constitution. However, on September 29, 1937, General Dutra released the so called “Cohen Plan” describing a detailed plan of the communist revolution.

The plan was a fabrication that Vargas used as a pretext to declare a state of emergency. On November 10, Vargas, in his radio address to the nation, announced that he took upon himself the dictatorship powers and it was sealed in the new Constitution.

Vargas called a halt to the presidential election, dissolve the National Congress, banned the oppositional political parties, established harsh censorship, created the centralized police, and filled prisons with dissidents while propagating nationalism and estsablishing control over the state policy.

Vargas’ “authoritarianism” was twofold. On the one hand, it allowed the dictator to perform the role of the “father of the peoples” (something many leaders of the time were used to doing). On the other hand, the image of the “people’s leader” allowed the president to balance out the interests of the two macro-regions. The thing is that Vargas came to power from the ruins of the old political system. In its form, this system was a normal republic. In its essence, it was a behind-the-scene deal made among the rich families of the two biggest regions in the South Brazil – Sao Paulo and Minas Gerais.

Later, this system became known as “coffee with milk” (café com leite) since Sao Paulo was the center of the coffee production and Minas Gerais – of the dairy industry. The name took despite its certain inaccuracy – the milk producers had never had any strong political power.

In its essence, it was an oligarch regime that was based on the system on the social patronage. This system is well described in the Godfather novel and shown in its famous adaptation. Relatives, neighbors, and simple acquaintances come to the head of the family to seek help in exchange for different favors.

In Brazil, the heads of these regional clans were called “colonels”. They solved all the problems and gave orders for whom to vote at elections. Thus, the political competition in the country was reduced to the strategic games among the “colonels” where they were independent players while politicians, state officials, and entrepreneurs, depending on the rules of the game, were used as pawns or consumables.

In an economy based on agriculture such a system can be quite sustainable. In essence, this is a normal feudal regime that, as we know, can survive for centuries. However, in the contemporary times, when the main production factors (labor and capital) have become mobile and can be quite responsive to the external changes, the sustainability of such a regime fades. And the power balance in Brazil collapsed, too, having become a victim of geopolitics.

WWI and the Great Depression had destroyed the world coffee market in its entirety. Facing the disappearance of the economic basis for their existence, the Sao Paulo aristocracy started withdrawing funds from agriculture and investing them in industry development. The old system of political consolidation based on the feudal system of patronage was destroyed but the necessity in the political control from the elite remained. Vargas was supposed to guarantee the new political balance and ensure the normal functioning of the united national economy. However, as often in history, the guarantor had slowly but surely turned into a dictator.

Note that Sao Paulo lost the battle with the regional elites but, eventually, became the center of the new economic policy and an important industrial hub of Brazil. This is how it remains today, too. And this circumstance is yet to play its role in the political history of the country.

Vargas’ Liberalization

The first step of the democratic transition in Brazil occurred immediately after WWII. This period was short but its influence on the country was an extremely negative one. Vargas himself was the one who chose to liberalize the regime and, in the spring of 1945, he declared an amnesty for political prisoners while allowing political parties to be active in the country.

In actuality, Vargas simply wanted to “legitimize” himself by using his enormous popularity among the Brazilian people. However, in a few months, he had become a victim of a military coup d’etat. His power was taken away by the junta that consisted of representatives of the military command.

On October 29, 1945, the extreme right-wing members of Vargas government, General Pedro Monteiro and General Eurico Gaspar Dutra, drove him from the office appointing Chief Justice of Supreme Court Jose Linhares Interim President. Soon, they held the presidential elections which Dutra won. Vargas supported his politics and, for this reason, was not exiled from the country. In 1946, Vargas was elected a member of the Rio Grande do Sul Federal Senate where he had served until 1950. He, however, did not actively participate in the Senate activities and was the only parliamentary who did not sign the new Constitution of 1946.

The military turned out to be surprisingly liberal. They did not execute Vargas and even let him be engage in the regional-level politics. However, they were soon to regret it. Having declared their intention to hold free secret elections, they, once again, collided with Vargas. The former dictator nominated himself and won effortlessly and, this time, by fair means.

Vargas returned to mainstream politics in 1950 when he participated in the presidential elections based on free and secret vote. Having received most votes, he assumed power once again, this time, as the nation-wide elected president. His popularity among the Brazilian people was the guarantor of his success.

Vargas took the familiar road: expanded oil production and metal industries, developed the national system of electricity provision, established the National Economic Development Bank. All this only ensured his power. However, in 1954, the situation worsened dramatically: the inflation rate grew resulting in the strikes of the workers who demanded wages increase. At the instigation of Vargas’ opponents, a crisis stroke. On August 5, it came to its climax when Major Rubens Vaz who had attempted to assassinate Vargas’ main competitor Carlos Lacerda was himself killed on Tonelero street. Lieutenant Gregorio Fortunato, the chief of Vargas’ personal security service, was accused of the assassination. It had triggered the discontent among the military, so the generals demanded Vargas’ resignation.

Vargas resisted until the very end. On August 24, he scheduled the ministers’ emergency meeting but received the news that the officers would not back down. So, he chose to retire – not from politics but from life – and shot himself in the heart at the Catete Palace. His suicide note had become well-known for its final sentences, “I take the first step to eternity. I leave life to enter history”.

Indeed, Vargas’ death marked the final point in the history of his regime. But, for the democratic Brazil, the journey was just beginning.

Democracy Wins

In 1955, Juscelino Kubitschek became the first democratically elected president of Brazil. Born in the Minas Gerais state, he was a truly popular leader.

Kubitschek had a medical degree. His political career started in 1934 when he became a member of the Minas Gerais Legislative Assembly. From January 31, 1950 to March 31, 1955, he served as the governor of his state. Despite the fact that Kubitschek as a politician developed during Vargus’ presidency, he held left-liberal views and spoke against the totalitarian form of state governance.

Kubitschek acted in complete accordance with the laws of the local policies: he gave many promises and launched the Plan of National Development that consisted of fast economic, educational, infrastructural reforms. The plan had a motto – “Fifty years of progress in five”. He is best known for building the new capital, the Brasilia city that was supposed to become the symbol of the new way of life. The capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasilia on April 21, 1960. Kubitschek is remembered in history as a popular, effective, and democratic leader.

War with Communism

Still, not everyone agreed on this opinion. The unclassified CIA data showed that, at that point, the agency was preoccupied with the possibility of the communists seizing power in Brazil. These concerns later became a real paranoia for the US. This paranoia had already buried quite a few democratic regimes in the region. Moreover, it was the paranoia and not the understanding of the real situation that had caused the events in Cuba when the typical regional leader became the “client” of the USSR even though, at first, no one could have predicted such a development.

Brazil, too, was a victim of this approach. Already in Vargas times, the data on the mythic “communist revanche” was appearing in the CIA reports. The watchful experts from the agency spotted communists among the dictator’s allies. Vargas’ attempts to distance himself from the oligarchs and to find support among trade unions were considered as a movement towards the communists who controlled these organizations.

Despite the fact that, in 1947, the Communist Party of Brazil was banned by the military junta, this decision did not lead to eradicating the communists from different spheres of the social life, say the authors of the National Intelligence Estimate published in 1955. The report appeared on the eve of Kubitschek’s accession to power. The analysts believed him to be a “left candidate under a strong influence of the communists”.

The Communist Party of Brazil consisted of about 100-120 people, by the CIA estimations. Its influence, however, was much stronger because the ideas of the “social equality” were actively distributed among different social groups, the NIE authors believe.

Even the quite successful and democratic Kubitschek’s presidency did not change the CIA ideological matrix of the 1950s according to which the traces of communist plots could be found in any event. They supposed that the “leftist coup d’etat” would inevitably move Brazil away from the US and towards the USSR interests. This type of thinking had become known as the “Domino theory”. It meant that any kind of conflict in the Third World countries should be regarded as an element of the global opposition between the USSR and the US, and this conflict could change the balance of power.

In regard to Brazil, the reestablishment of the diplomatic relations with the USSR was the crucial moment in testing this theory. After 1917, the diplomatic ties were cut off because of the Russian revolution. They were reestablished in 1945, but cut off again in 1947.

Yet another attempt to reestablish the diplomatic ties was made by the new president of Brazil Janio Quadros in 1961. He took the power as a result of the first Brazilian true democratic transition.

Quadros was able to mobilize the left forces on the platform of his image as the people’s leader and won the 1960 election having literally destroyed the opposition, the Christian Democratic Party.

Quadros had a law degree. He began his political career in 1950 when he became a member of Sao Paulo municipal government. In 1953-1954, he served as the mayor of this city. In 1954, he became the governor of the state and remained in his position until 1958. He became President of Brazil on January 31, 1961.

Quadros paid too high a price for his decision to reestablish the diplomatic relations with the USSR (and, in addition, with Cuba). He immediately lost his political support in the Parliament after which, his powers diminished. On August 25, 1961, after eight months of his presidency, he wrote a resignation letter.

It was a strange document. The president said his resignation had to do with the influence of some foreign and “occult” forces. And if we know what the first ones were, we are at a loss as to the role the second ones played in the history of the fall of the Brazilian democracy.

Quadros’ policy was not liked either by the US and the financial elite or by the Brazilian military bosses. A new political crisis began. On August 24, 1961, they broadcasted Carlos Lacerda’s address to the people. In it, the governor of Guanabara announced that a coup d’etat was being prepared in Brazil and the president no longer had real power. Quadros’ resignation letter was made public the next day. In this letter addressed to the Parliament, Quadros striped himself of his own powers.

Whether accidental or not, at the time of Quadros’ resignation, Vice-President Juan Goulart was in China on an official visit and could not assume the presidency. The vacuum was promptly filled by the head of the House of Delegates Ranieri Mazzilli who served as President for a couple of weeks. It was enough, however, to adopt the Constitutional amendments that significantly limited the presidential powers.

Having ascended to power in September 1961, Goulart discovered that the country had turned into the parliamentary republic. The main political was performed by the prime-minister. The Parliament was celebrating without even suspecting that it had just buried not just the presidential republic but democracy itself.

Cultural Counterrevolution

As it could be expected, Juan Goulart started his rule with a campaign to restore the former presidential powers.

He succeeded in introducing this question on a referendum which he won thanks to the strong support of the people. In January 1963, 80% of the population voted in support of the strong presidential power.

Juan Goulart graduated from college in 1939 having received a doctorate degree in jurisprudence and social sciences. He began his political as Getulio Vargas’ supporter. From July 1953 to February 1954, he served as the Minister of Labor, Industry and Trade. In 1955-1961, he served as Vice-President of Brazil, first, under Juscelino Kubitschek and then, under Janio Quadros.

Having assumed the presidency, Goulart started radical reforms in the economy and the social sphere. As a result of the agricultural reforms, all the unused farm lands whose area exceeded 600 ha had to be eradicated and redistributed among the landless population. At the time, the number of villagers exceeded the number of city people in Brazil. Therefore, for Goulart, this reform guaranteed the majority of votes at any election. Moreover, the president also implemented the electoral reform giving the right to vote to the illiterate people and the military officers of the lowest ranks.

Goulart’s decision to allocate 15% of all the state expenditures to the sphere of education made him even more popular. This innovation was supposed to help to eradicate illiteracy within the shortest possible time.

The tax reform was supposed to ensure the state income growth. The reform significantly limited the possibilities to siphon funds off the country. At the same time, the mining concessions were revised, too.

Not surprisingly, all these undertakings had caused the discontent among the “serious people” both in the country and in the US that still regarded Brazil as the sphere of its special interests. One of the CIA secret memorandums prepared for the highest authorities in 1963 contained a prediction on Goulart’s inevitable transformation into a populist dictator who would surrender his power to a coalition of the communists and the extreme nationalists.

Despite the fact that the Communist Party of Brazil had remained a banned organization since 1947, the authors of the memorandum believed that this ban was of a strictly formal nature and the communists still had their influence in the country. As for Goulart, the experts thought him to be incompetent both as a politician and an economist. They did not exclude a possibility that he would have to face a serious opposition. The role of the opposition could be performed by the main political force of the Latin American countries, the army.

The analysts turned out to be quite perceptive. In March 1964, protests and marches began. The participants spoke against Goulart’s reforms. They had a slogan – “For Family, God, and Freedom”. The protests shapeshifted into an open revolt and Goulart was forced to leave the country. The military took the power and kept it till the mid-80s.

Manhunt on Democrats

One of the leaders of the 1964 coup d’etat, Head of the Brazilian General Staff Castelo Branco, was the first president of the Brazilian military government. He did not plan to remain the president for long and was preparing to devolve the power on civic persons. But on July 18, 1967, Branco was killed in an airplane accident and his powers were delegated to a different military officer, Artur da Costa e Silva.

There were no more attempts to delegate power to a civic government. Moreover, the military banned many democratic politicians from assuming positions in mainstream politics. Some were even assassinated. For example, on August 22, 1976, the automobile of Juscelino Kubitschek who had decided to return to Brazil ran into a bus and, in December 1976, Juan Goulart died in Argentina.

The Brazilian military did not find anything suspicious in these deaths. Only much later, it became known than both ex-presidents were victims of the so called “Operation Condor”. It was a series of “events” carried out by the joint forces of the Latin American dictators whose purpose was to destroy their political opponents. The methods employed were quite various and included the ones used by terrorists. The “events” took place in different countries including the US.

Nowadays, we are aware that the 1964 coup d’etat that destroyed the achievements of the democratic transition in the country and delayed the new democratic attempt for 20 years happened thanks to the hidden but tangible assistance of the US at the political and military levels. Later, it became apparent that the US secret service knew about Operation Condor but chose not to prevent the assassinations of the oppositional leaders. Perhaps they were being guided by the highest geopolitical interests of the time.

Anyway, the “romance” between the US and the military dictators was a purely strategic one and ended as soon as the communist threat had disappeared. And the next step of the transition from authoritarianism to democracy in Brazil happened in a very different way.

To be continued