By the middle of the 21st century, the North and the South of Kazakhstan will become a part of the South Kazakhstan. This demographic transformation will inevitably lead to a socio-economic one with a change of the economic structure and creation of new elites. You think this is non–feasible? We are not so sure.

In the article called “The Seven Trends that Will Change the World”, we demonstrate the National Intelligence Council analysts’ prognoses presented in the “Paradox of Progress” report. These seven trends, the NIC analysts believe, are going to determine how the world civilization will develop in the future decades.

Today, we are offering you the first article from the “Global Trends.KZ” series. As we had promised, we had researched each of these trends through the prism of the Kazakhstan realia as it allows for a better understanding and evaluating the country’s prospects in the context of the global change.

The Future Comes from the South

We are going to start our “Global Trends.KZ” project with a discussion on demography. It is no secret that demography had always been and still remains the basis for all long-term prognoses and scenarios. It is no coincidence that demography is called the “delivery nurse” of all revolutions because demographic shifts are the main driver for social changes in any society.

Take, for instance, the African or Arab countries where, upon improving the general sanitary conditions and reducing infant mortality, the unchanged birth rates led to increasing the percentage of the young and jobless part of the population that rushed to the cities to join the ranks of the poorly qualified tradesmen. On the other hand, there is the USA that, after the WWII, had also experienced the baby boom. So, in the 1960s, the US cities had also been overflown with the young people searching for jobs and justice.

In both cases, the demographic factors led to social protests that turned out to be a real challenge for the political systems of these countries and then, consequently, led to their change. Now the world is about to go through yet another such change as well.

The rich get old, the poor are not. This development paradox is mentioned among the first in the NIC’s report. This is a consequence of diverging demographic trends. In the rich countries, the economically active population (EAP) is shrinking (note that China and Russia are experiencing the same trend). However, the EAP cohort is growing in the developing countries, particularly in Africa and the South-East Asia.

This global trend will result in the following:

- urbanization,

- general employment growth,

- “pressure” of the social obligations guaranteed by the state,

Creating a supplementary education system may help to amend the situation.

Let us consider this problem in the context of the Kazakhstan realia.

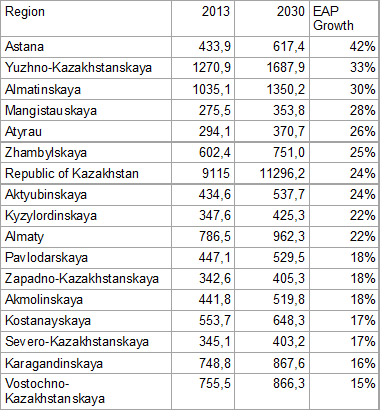

The population in growing, including its economically active part. Based on the Ministry of Economy and Budget Planning’s data, by 2030, the EAP of Kazakhstan will grow by 24% surpassing the growth rate of general population.

Regionally, this growth looks like this.

EAP Growth by Regions

Source: Ministry of Economy and Budget Planning’s report “The Demographic Prospects of Kazakhstan: Major Trends, Challenges, Practical Recommendations”.

Astana is the absolute leader in the EAP growth rate which is logical for the country with a supra-centralized management of its economy and business (including private enterprise). The Southern regions hold the second and the third places. They are also the leaders among the poorest ones.

Poverty in Kazakhstan has a clearly marked geographic nature. The leaders in the poverty headcount are the Yuzhno-Kazakhstanskaya region (4.6%) and the Zhambylskaya region (3.3%). The richest territories are the Karagandinskaya region (0.6%), the Astana and Almaty cities (0.7%).

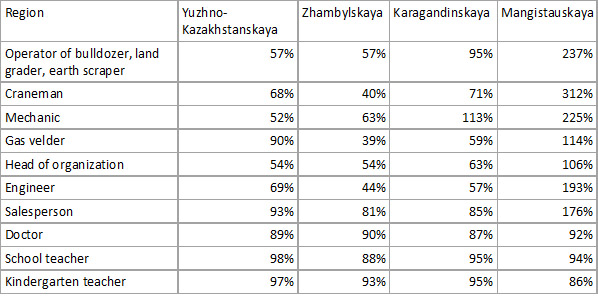

Despite the significant differences in the estimates, the dissimilarities in the salary size are not so big among the regions (see the Kazstat data below).

Wage Differences in Some Kazakhstan Regions*

*for some categories, wages shown in percent from average

Thus, the difference between the poor and the rich comes not from the labor market oversupply but from the structural characteristics of the labor market itself where the supply of unqualified labor force prevails, and this force cannot compete at the skilled labor market.

Migration is one of the most obvious explanations for that. Based on the Ministry of Economy and Budget Planning’s data, in the period from 1991 to 2013, 246 603 families had come to Kazakhstan and received the oralman (ethnic Kazakh repatriate) status. This amounts to 924 363 ethnic Kazakhs. Most of them (61% of the entire number or migrants) came from Uzbekistan and settled in the South, in the Yuzhno-Kazakhstanskaya region (21.3%), Almatinskaya region (16.1%), and the Zhambylskaya region (9.4%).

“The oralmans often do not have enough education and professional skills which affects the level of their adaptation and integration into the social, economic, and cultural live of the country”, the Ministry of Economy and Budget Planning officials say in their report.

70.8% of those who came to the country had a high school diploma or no education at all. Consequently, their settling inside the country depended not on the labor market demands but on how close the settlement place was to their country of origin. After the oralmans, the other ethnic groups come to Kazakhstan, those who had connections with the previous generations of migrants. Thus, the Uzbek and Uygur populations grew. In 2010 alone, the pure migration rate of the Uzbek population to Kazakhstan increased by 51.3%. In 2011, the pure migration rate of the Uygur population increased by 29%.

Based on the official estimates, the net result of the migration processes in Kazakhstan amounts to substituting the highly-skilled labor resources by the poorly-skilled ones. This is worsened by the Eurasian Union labor market mechanisms that allow to simplify the rotation of the labor force inside the union.

The growth of the EAP without employment prospects means a future revolution in the country provided that all the other elements of the socio-economic system remain unchanged and the regional differences are preserved. This is a very serious supposition bearing in mind the global demographic trend (using the NIC researches’ vocabulary).

Here is the essence of this trend. The Southern territories of the country, from local regions, will transform into Kazakhstan’s loadbearing construction. The long-term prognosis offered by the Akorda specialists testifies in favor of this hypothesis. The authors suggest that, in 2050, the population of Kazakhstan will amount to about 24.5 mln. Of that number, about 10 mln (or 40% on the entire population) will be living in the Almatinskaya, Dzhambylskaya, and Yuzhno-Kazakhstanskaya regions.

In other words, by the middle of the current century, the North and the West of Kazakhstan would rather be considered a part of the South Kazakhstan and not the other way around. Moving the capital to the North will hardly stop the process. The demographic shift will inevitably lead to a socio-economic one with a change of the economic structure and creation of new elites.

The paradox here is that this, at the first glance, negative scenario of Kazakhstan’s civilizational shift from Central Asia to South Asia (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) may give it more stability and a wider social platform for development. It may, however, pull the country down to Dark Ages as well.