The National Intelligence Council analysts’ prognosis that the future will inevitably form new identities threatening the established world order finds its, however strange and frightening, confirmation in the Kazakh realia.

One of the globalization paradoxes lies in the fact that expanding the connections between different social groups may lead not to their coming closer together but to splitting-up the existing players instead. The NIC experts note this tendency in their recently published “Paradox of Progress” report (ссылка на доклад «Парадоксы прогресса»). And Kazakhstan may serve exactly as an example of such development.

Global Aul

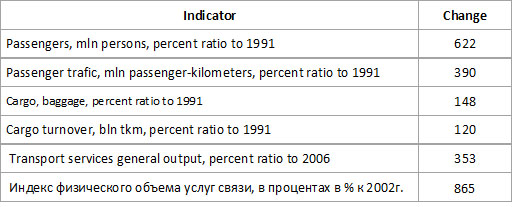

Since Kazakhstan received its independence, the country had been taken by the globalization storm. This conclusion can be reached by analyzing the usual indicators – the rates of the trade, transport, and communications development. Judging by these indicators, the growth Kazakhstan is demonstrating is more than reassuring.

For instance, the number of passengers in 2016 increased more than six times compared to the 1991 data (even though the majority of the travelers still consists of the officials and the businessmen visiting the capital, the growth is very impressive).

Source: Kazstat

Although the statistics shows that more people are currently included in the common goods and information exchange system, the sociological data proves that the nation is now, in fact, disintegrated as a large unified community. And, as some indicators demonstrate, this disintegration process is speeding up.

“Strategia” (a Kazakh center for social and political research) has been studying the Kazakh citizens’ identity since the beginning of the 2000s by using the sociological survey method. The last of these surveys was conducted in 2014. Reporting its results, the “Strategia” president Gulmira Ileuova spoke about the disintegration. If in 2004 and 2009, the Kazakh citizens named their country as their primary identity, in 2014, 75.7% of the survey participants identified with their towns or villages.

This local identity, Ileuova argues, had become the most widespread one in the “body of our society”. Identifying with the place of residence is usually explained by high transport and information costs. When they are decreased, nations are formed. The language unity is considered the main condition for forming a national ideology. Thus, in theory, expanding the Kazakh language usage sphere should have strengthened the national identity. In reality, however, it had led to further disintegration and dividing the society into the “locals” and the “globals”.

Digital Divide

We know all too well that the Internet can not only bring people closer but set them apart as well. The term “digital divide” has long been used to underscore the very depth of the abyss that separates those who have access to the global information resources and those who do not. In Kazakhstan, however, the divide is of a very different nature.

The Kazakh are doing quite well in terms of the Internet access. The divide lies in the language. There is about a billion sites in English. There are about 100 hundred million sites in Russian. And less than 20 thousand in Kazakh. Thus, those who know only the latter have no chance to compete in the digital world.

Based on the data gathered by the Russian Strategic Research Institute (RSRI) associated with the Russian secret service community, the Kazakh internet-audience prefers using Russian both as the domain and the spoken language. The “.com” (40%) and “.ru” (40%) domains have practically cut the Kazakh internet-audience in half. However, even in the “classic” Kaznet (the “.kz” and “.kaz” domains), the Kazakh language content does not exceed 12% that mostly include the state media and state agencies sites.

As oppose to the traditional media, the Internet does not uphold the language law so the materials do not have to be published in Kazakh. And Kazakhstan itself is not too big and attractive a market for advertising to make exceptions for it. Therefore, the country and the information community are now moving in different directions.

In this situation, the state’s desire to make English an obligatory subject in schools is quite understandable. This is how they want to escape the existing information trap. However, the very idea that Kazakhstan may transform into the Netherlands of sorts where everyone understands English seems utopian. At best, we will have a new and smaller copy of India where the knowledge of the English language works as a social divider. The existing social trend may lead to forming the “digital Russians” and the “digital English” groups in Kazakhstan that will join the ranks of the “offshore aristocracy”. For them, Kazakhstan will no longer be their country but the territory where they happen to live.

Social Mobilization

Apart from the language demands, the contemporary national patriots in Kazakhstan have no ideology that can form the civic identity among the Kazakhs. In the first Soviet decades followed by the mass decolonization era in Asia and Africa, nationalism had been allying with the leftist ideology. Forming a civic nation was considered a most important step on the way of creating the unified classless society. Thus, the social utopia was, in fact, working well for forming national identities.

In 1970s, a religious factor had come into play as well (mostly, the Islamic one), and the system had transformed into a triangle. The relations had become more complex. In general, however, Islam as a global religion had played rather a negative role in the East’s countries national development. In that regard, it was not much different from Catholicism in Europe that, too, aspired to the global role but suppressed forming the nations.

In Russia and Turkey, where religion is the national and not the global factor, the US analysis believe, there is a threat of forming a “double” identity (religion+nation) that can become the “big-time politics” instrument in the hands of the rulers.

In Kazakhstan, where 70% of the population consider themselves Muslim, the religion factor does not play the role of a mobilizer. Moreover, it rather contradicts the national interests since the Salaphites – the most active social Muslim group – do not support the ruling authority and even go against it. The geographic concentration of the Salaphites in the Western part of the country (Magnitau, Atyrau, Aktobe regions) promises nothing good in the future. Therefore, we should not be surprised by the fact that the Kazakh authorities prefer to label all the Salaphites as terrorists thus strengthening a special identity of this influential social group.

Past Ahead

The loss of the civic identity threatens to send the Kazakh civilization back to the past. This scenario is, in fact, a quite plausible one. The idea that history is inevitably a progressive movement is one of the most widespread misconceptions shared even by educated people.

Based on this idea, history is (though not quite linear) but still a more or less steady process of the human civilization development. Even the collapse of the Roman Empire in Europe is taught in schools as making a new step in the human evolution and not entering the “dark Middle Ages”.

In truth, the “big history” is a whirlwind that had created and destroyed powerful civilizations in the course of the millennia. Central Asia is a clear example of it. In the 11th-12th centuries, this region had a real chance to become a birthplace of a world civilization Renaissance. Instead, it went into a deep lethargic sleep that had lasted for several centuries.

Little by little, the archaic issues are becoming the center of the social agenda in Kazakhstan. The problems of the modernization are left to the authorities as the society prefers to tell tales about the great mythical past and does not seem to mind entering it.

*Read the previous articles of the Global Trends.KZ series here: Where is Kazakhstan going?, Global Trends. KZ. The Future Comes from the South, Seven trends that will shake the world.