One of the key sections of the report of the world bank on global development 2017: “Government management and the law” is dedicated to national elites and their role in government administration. It is called: “When political will is not enough: power, negotiations and arena of political actions.

Below we will quote key points from the review of the report in Russian language. (On the subject read Where do revolutions come from and What restrains forward movement).

- “This Report argues that institutions perform three key functions that enhance policy effectiveness for development: enabling credible commitment, inducing coordination, and enhancing cooperation. But why are policies so often ineffective in doing so? A typical response among policy practitioners is that the right policies exist, ready to be implemented, but that what is missing is political will in the national arena. This Report argues that decision makers—the elites —may have the right objectives and yet may still be unable to implement the right policies because doing so would challenge the existing equilibrium—and the current balance of power. Thus the balance of power in society may condition the kinds of results that emerge from commitment, coordination, and cooperation”.

- Ultimately, policy effectiveness depends not only on what policies are chosen, but also on how they are chosen and implemented. Policy making and policy implementation both involve bargaining among different actors. The setting in which (policy) decisions are made is the policy arena—that is, the space in which different groups and actors interact and bargain over aspects of the public domain, and in which the resulting agreements eventually also lead to changes in the formal rules (law). It is the setting in which governance manifests itself.7 Policy arenas can be found at the local, national, international, and supranational levels. They can be formal (parliaments, courts, intergovernmental organizations, government agencies), traditional (council of elders), or informal (backroom deals, old boys’ networks).

- Who bargains in this policy arena and how successfully they bargain are determined by the relative power of actors, by their ability to influence others through control over resources, threat of violence, or ideational persuasion (de facto power), as well as by and through the existing rules themselves (de jure power). Power is expressed in the policy arena by the ability of groups and individuals to make others act in the interest of those groups and individuals and to bring about specific outcomes. It is a fundamental enabler of—or constraint to—policy effectiveness (box O.3).

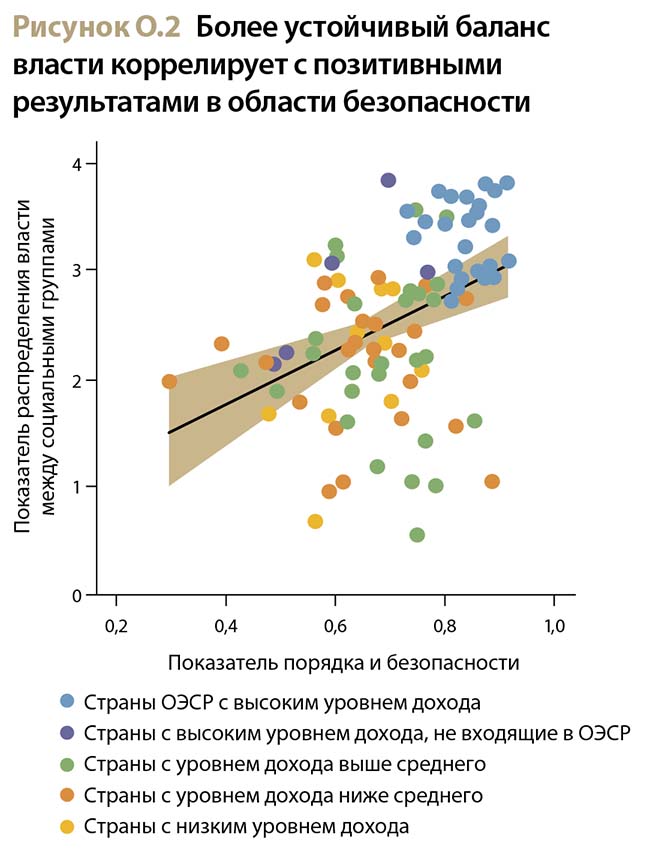

- The distribution of power is a key element of the way in which the policy arena functions. During policy bargaining processes, unequal distribution of power—power asymmetry—can influence policy effectiveness. Power asymmetry is not necessarily harmful, and it can actually be a means of achieving effectiveness, for example, through delegated authority. By contrast, the negative manifestations of power asymmetries are reflected in capture, clientelism, exclusion.

- Exclusion. One manifestation of power asymmetries, the exclusion of individuals and groups from the bargaining arena, can be particularly important for security (figure O.2). When influential subjects are excluded from the political arena, some individuals and groups may consider violence a preferred and even rational method of standing up for their interests, as it happened in Somalia. As a result, actors in the bargaining arena may end up not achieving a compromise (as it happens, for example in case of peace bargains between rival factions, or when disputing parties fail to reach an agreement)”.

- Capture. A second manifestation of power asymmetries—the ability of influential groups to “capture” policies and make them serve their narrow interest— is helpful for understanding the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of policies in promoting long-term growth. The effects of capture can be quite costly for an economy. Politically connected firms are able to obtain preferential treatment in business regulation for themselves as well as raise regulatory barriers to entry for newcomers—such as through access to loans, ease of licensing requirements, energy subsidies, or import barriers. Such treatment can stifle competition and lead to resource misallocation, with a toll on innovation and productivity.

- Although it is possible for economies to grow without substantive changes in the nature of governance, it is not clear how long such growth can be sustained. Consider the case of countries apparently stuck in “development traps.” Contrary to what many growth theories predict, there is no tendency for low- and middle-income countries to converge toward high income countries. The evidence suggests that countries at all income levels are at risk of growth stagnation. What keeps some countries from transitioning to a better growth strategy when their existing growth strategy has run out of steam? With a few exceptions, policy advice for these countries has focused on the proximate causes of transition, such as the efficiency of resource allocation or industrial upgrading. The real problem, however, may have political roots: powerful actors who gained during an earlier or current growth phase (such as the factor-intensive growth phase) may resist the switch to another growth model (such as one based on firm entry, competition, and innovation in a process of “creative destruction”). These actors may exert influence to capture policies to serve their own interests. Box O.4 presents an example of the political challenges in transitioning toward a different growth strategy—one that is related to investment in environmental sustainability.

- Clientelism. A third manifestation of power asymmetries is clientelism—a political strategy characterized by an exchange of material goods in return for electoral support.13 This strategy is helpful for understanding why policies that seek to promote equity are often ineffective. Although pro-equity policies can be potentially beneficial for growth in the medium and long run, they can adversely affect the interests of specific groups, particularly in the short term. Those affected by equity-oriented policies may be concerned about losing rents or about seeing their relative influence reduced, and thus they may attempt to undermine the adoption or implementation of those policies. When societies have high levels of inequality, such inequalities are reflected in the unequal capacity of groups to influence the policy-making process, making inequality more persistent. Clientelism leads to a breakdown of commitment to long-term programmatic objectives, where accountability becomes gradually up for sale.

Paragraphs cited above form the review of World bank’s report, once again prove that Kazakhstani problems are not unique. Thus, directions in which governments and ruling elites must move in order to overcome them are also similar. However, a particular set of methods, solutions, mechanisms, decisions, ideas, etc. will be unique for each country.

As of today, in Kazakhstan, those who answer for making the decisions – elites, may formulate goals correctly, but at the same time “may still be unable to implement the right policies because doing so would challenge the existing equilibrium—and the current balance of power”. Thus the “balance of power in society” – determines to which results commitment, cooperation and coordination will lead”. In our Kazakhstani society they lead to nothing.

Reasons why this happens are widely known and aren’t contested by anyone even Akorda. In the nineties concentration of power in the hands of one person and people, that comprised his inner circle, largely helped in overcoming of post-Soviet social, economic, political crises in Kazakhstan. Thus, “power asymmetry is not necessarily harmful, and it can actually be a means of achieving effectiveness—for example, through delegated authority”. Later however, power asymmetry has rusted, became self-sufficient, oriented exclusively at self-preservation and keeping certain individuals in power: “On the contrary, among negative manifestation of power asymmetry are capture, clientelism and isolation”.

The fact is that “the distribution of power is a key element of the way in which the policy arena functions. During policy bargaining processes, the unequal distribution of power—power asymmetry—can influence policy effectiveness” is now recognized by many in Kazakhstan but hasn’t become important for the ruling elites yet. Largely, because it is low grade, since it is concerned not with self-preservation, i.e. considering the long-term time period, but rather with self-survival, i.e. now and today.

Once again we state, that experts of the World bank in their report “Government management and the law” could have easily limited themselves with reference to the practice of an individual country, specifically republic of Kazakhstan, in order to illustrate how isolation, capture and clientelism bring gigantic harm to countries, national economies, political systems and the population. Looks like ahead of us is a time of clarification of who’s guilty – an unavoidable stage in development of any government or political system at the stage of stagnation.

The World bank has underlined culprits in the following way: The real problem, however, may have political roots: powerful actors who gained during an earlier or current growth phase (such as the factor-intensive growth phase) may resist the switch to another growth model (such as one based on firm entry, competition, and innovation in a process of “creative destruction”). These actors may exert influence to capture policies to serve their own concerns”.

For now, in search of culprits, Akorda is actively trying to deflect the attention to higher up corrupt officials and poorly functioning top-managers, however, it is becoming harder and harder to do so. Evidently, the growth of dissatisfaction and protest moods in Kazakhstan will continue, and when it will stop, is impossible to predict. The other things is that it will not spill over into mass public campaigns, that are severely suppressed by the regime and organizers of which are demonstratively purged. But that is quite a nominal preservation of internal political stability, since Kazakhstanis are starting en masse search of new wats of solving their problems. In particular, the most active part is emigrating, and the less active part – shut itself off from the country, refusing the regime in any support.

*World bank. 2017. Report on the global development 2017. Government management and the law. Review. World bank, Washington, D.C. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO