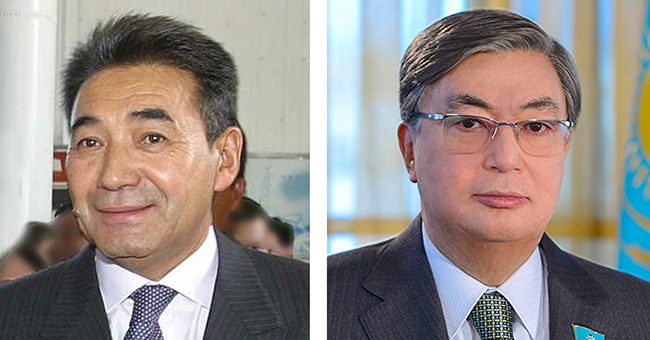

On the eve of the parliamentary elections, Nursultan Nazarbayev fired Prime-Minister Nurlan Balgimbayev appointing Kasymzhomart Tokayev who, at the time, served as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Tokayev’s appointment confirms the fact that, in general, the reforms had been completed and that the president no longer needed the strong and independent technocrats.

…This year, the immortal president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, turns 77. Anticipating this event, we have started publishing his biographical essay “Nursultan Nazarbayev. Stages of Career, System of Interests, and Political Power”. It was written in 2005 by a famous Kazakh scholar, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Nurbolat Masanov for the civic society activists and have never been published before.

Nursultan Nazarbayev. Consolidation of Power

On the eve of the parliamentary elections, Nursultan Nazarbayev fired Prime-Minister Nurlan Balgimbayev appointing Kasymzhomart Tokayev who, at the time, served as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Tokayev’s appointment confirms the fact that, in general, the reforms had been completed and that the president no longer needed the strong and independent technocrats such as Kazhegeldin or Balgimbayev. It looked like the days of the other technocrats who had dominated the government structures were numbered as well.

During the several years that followed, practically all the technocrats were removed from the power structures. It was due to the fact that the first decade of Kazakhstan’s independence had formed a new class of state officials – the professionals with a substantial state management experience.

In December 1999, as suggested by Nazarbayev, new speakers for both parliamentary houses were appointed – Oralbay Abdykarimov for the Senate and Zharmakhan Tuyakbay for the Mazhilis (the Lower House). They were supposed to act as President’s puppets. And if with Abdykarimov, Nazarbayev made no mistake in this matter, Zharmakhan Tuyakbay, in fact, turned into his serious political opponent in the course of several years.

In June 2000, the Civic Party of Kazakhstan presented a bill called “On the First President”. According to this bill, Nazarbayev was guaranteed to have the lifetime right to address the Kazakh nation, the state agencies and officials with initiatives and recommendations on the most important aspects of the Kazakh society development.

The First President was guaranteed the right to participate in the parliament and government discussions of important topics, to serve as the head of the Assembly of People of Kazakhstan, to be a member of the Security Council, to annually award the Peace and Progress Prize, to make suggestions on the personnel policy, on the imposition of the state of emergency, on the use of the armed forces, etc to the acting president.

At that, opposing the First President’s authorized activities would be prosecuted under law. The First President has immunity and cannot be responsible for the actions that have to do with carrying out his authority with exception of high treason. The First President has the right to refuse to testify in a civil or criminal case as well.

The First President and his family members will have a lifetime place of residence, office, security, transportation, free medical care and sanatorium-resort treatment, state insurance, pension amounting to 80% of the acting president’s salary, and other privileges. The First President’s family members would have the same service package. Also, with the use of the state budget resources, the First President would have his own fund, personal library, personal archives, and museum.

In July 2000, the bill was signed by Nursultan Nazarbayev. This had left no doubts about Nazarbayev’s fear of his political oblivion and showed his desire to have at least some institutional and legal guarantees on his future security.

Passing this law also served as Nazarbayev’s answer to the US criminal case against his advisor James Giffen accused of bribing the Kazakh state officials including Nurlan Balgimbayev and Nursultan Nazarbayev to promote the interest of the Exxon-Mobil corporation.

Fearing the accusations of authoritarianism, in August 2000, Nursultan Nazarbayev was planning to imitate some kind of the national political dialogue. The idea was introduced by the oppositional Forum of Kazakhstan’s Democratic Forces at the end of 1999. However, the democratic opposition of Kazakhstan refused to have a dialogue with the authorities without discussing its format first. They also demanded the immediate and unconditional amnesty for their political leaders which was not on Nazarbayev’s agenda.

Later, he did manage to implement the imitation model of a political “dialogue” in the country – first, in the form of the so called permanently acting committee on discussing the further democratization and development of the civic society led, from November 2002 to June 2004, by Baurzhan Mukhzmedzhanov, a vice-president representing the siloviki bloc, and later, from November 2004, in the form of National Presidential Committee on Democracy and Civic Society led by the National Security Council secretary Bulat Utemuratov. Both projects were boycotted by the democratic opposition of Kazakhstan.

At the end of September 2001, at the start of the international campaign against terrorism in Afghanistan, Nazarbayev, fearing to find himself in the political and international isolation, gave the official permission for the allies to use the Kazakh military bases, aerodromes, and air space to bomb the terrorists’ bases in Afghanistan.

In August 2001, Kazakhstan initiated an absentee trial against the main (for that time – kz.ezpert) Nazarbayev’s opponent Akedzhan Kazhegeldin that resulted in a very predictable 10 year jail sentence.

In Autumn 2002, a very serious conflict emerged between the omnipotent Nazarbayev’s son-in-law Rakhat Aliyev who had been using his position of the National Security Agency’s deputy chief to racketeer many of the entrepreneurs and a group of young technocrats and regional leaders who had started to lose their influence in Nazarbayev’s circles.

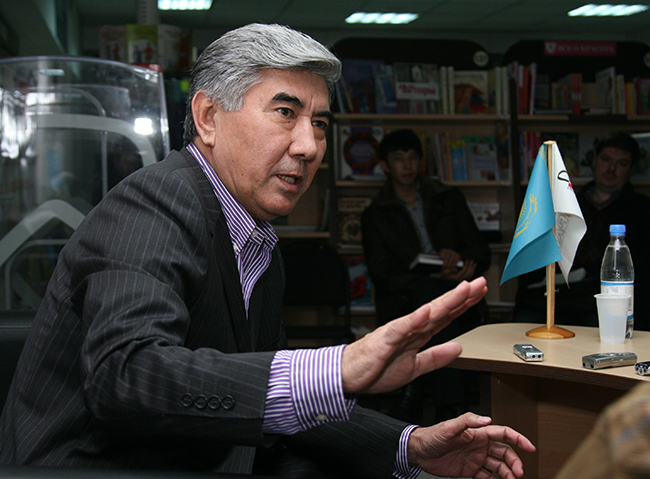

The bourgeoisie group fighting against Aliyev was led by the governor of the Pavlodar region Galymzhan Zhakiyanov and a representative of the big business, a former Minister of Energy, Industry and Trade Mukhtar Ablyazov.

They were supported by a former Vice-President Uraz Dzhandosov, the deputy of Minister of Defense Zhannat Ertlesov, a Mazhilis deputy Tolen Tokhtasynov, a famous entrepreneur Bulat Abilov, a former minister Alikhan Baymenov, and others.

As a result of this open conflict in the power structures, a new political agency was born, a civic movement called the Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan.

During November 2001, President Nursultan Nazarbayev fired most of those involved in the conflict. Those most persistent, Galymzhan Zhaliyanov and Mukhtar Ablyazov, became figurants of the criminal cases that ended in imprisonment of the presidential opponents.

Encountering the open and public confrontation of the two elite groups, Nazarbayev showed to the whole world that he was capable of making tough decisions and tried to suppress the technocrats’ protest at its very source.

Turning to the practice of open repressions, Nazarbayev was trying, on the one hand, to scare off his opponents and, on the other hand, hoping to consolidate the political elite around himself. For that purpose, he formed a new cabinet.

On January 28, 2002, Prime-Minister Kasymzhomart Tokayev who supported one of the fighting parties was dismissed. On that same day, Imangali Tasmagambetov, a neutral figure in relation to both conflicting parties, was appointed the new prime-minister. His task was to consolidate and pacify the political elite since the conflict had already caused a serious political chaos.

Nazarbayev’s tactical error that led to losing control over his family members and, most importantly, to allowing for a wide discussion about his political successor was the main reason for the elite crisis escalation in Autumn 2001. And if before all the political and business elites were, essentially, consolidated around Nazarbayev’s persona, now, the mere discussion about his successor has escalated the situation and triggered a series of conflicts. Now, the elite has begun positioning itself in relations to different possible successors which immediately caused it to break into separate groups.

Nazarbayev had, indeed, learned from this incident for he prohibited the elite from discussing a possible successor and, to avoid new conflicts, failed to elect his ambitious daughter Dariga in the September 2004 parliamentary elections.

The problem of Nazarbayev’s political successor was, therefore, put to rest.

Trying to divert attention from the political conflicts between the technocrats and one of his family members and from the political repressions that followed, Nazarbayev warned his cabinet that those who had not yet transported their families to the new capital Astana had to do it by the 8th of March 2002, otherwise, they should resign from their positions. In this way, Nazarbayev had showed everyone that, for him, Astana was his life’s most important project after the creation of the national state.

Read also: Nursultan Nazarbaev: career, interests, power, Nursultan Nazarbaev. Ascension to the top, Nursultan Nazarbaev: A focus on ethnocracy, Nursultan Nazarbaev: elimination of opponents.

Perhaps some of these materials present a subjective view of the first president’s persona. However, this view is, undoubtedly, worthy of attention of anyone who is interested in the history of Kazakhtsan.