The recent tensions in the relationship between two countries of the Central Asian region – Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan – have, in fact, a far more serious foundation that it may appear to the casual observer. First and foremost, this is about the systemic differences in their economies and political systems’ peculiarities that result from these differences.

We will start by saying that the two counties are incomparable size-wise. If the size of the Kazakhstan population is three times greater than that of Kyrgyzstan and if the size of the Kazakhstan territory is 13 times greater than that of Kyrgyzstan, then, as far as the GDP (the main indicator of the economic activity) is concerned, the difference between the counties is abysmal.

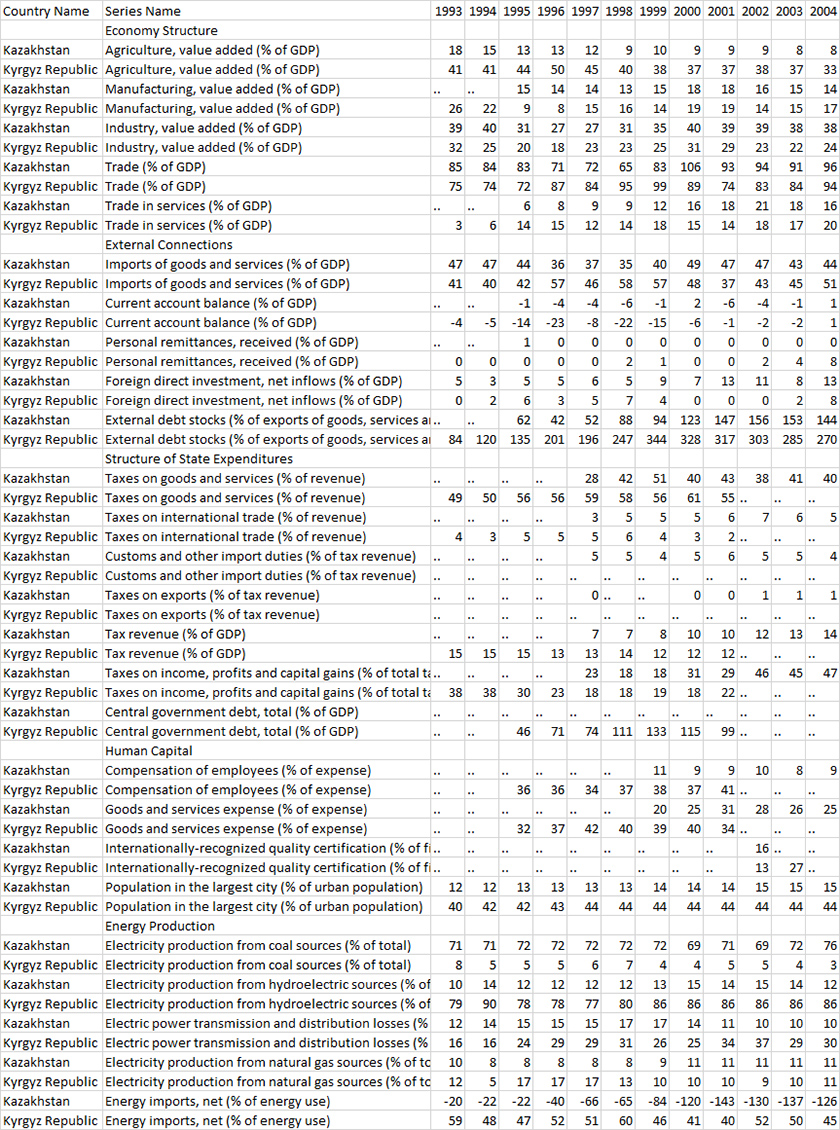

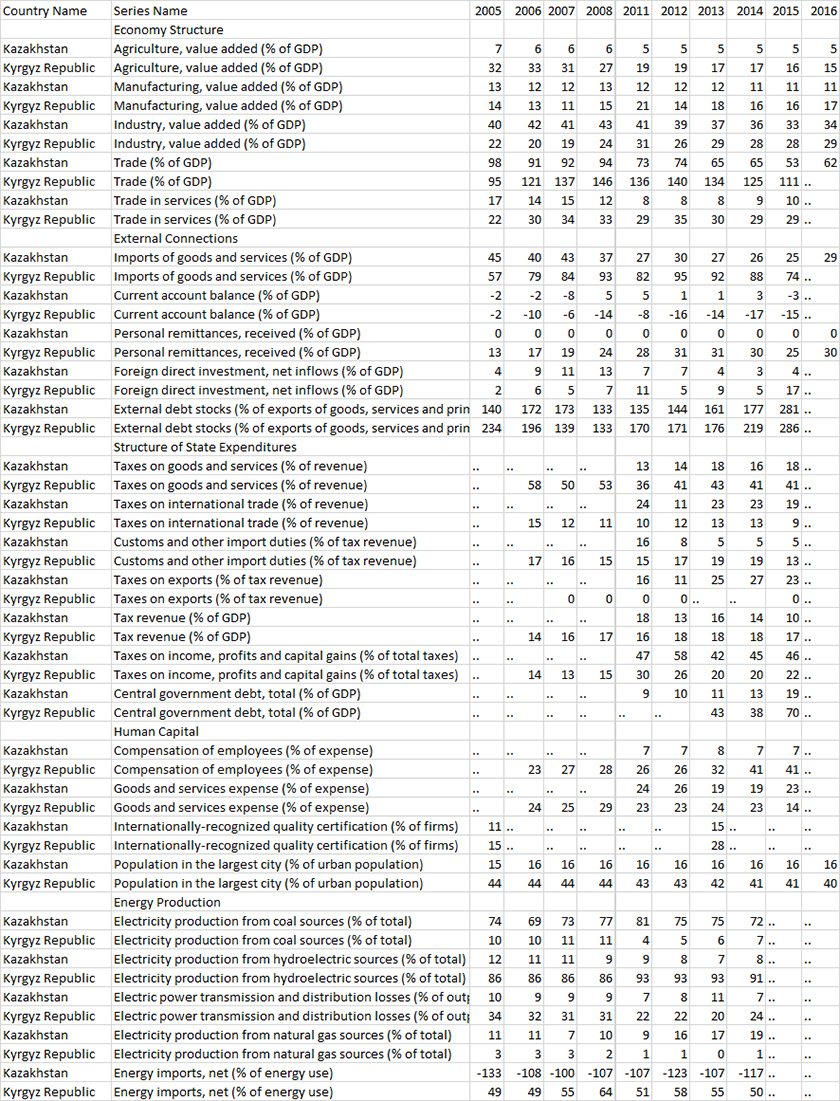

Kazakhstan’s GDP is 30(!) times bigger than Kyrgyzstan’s. Moreover, during the years of independence, this gap has become even greater. In the beginning of the 1990s, immediately after the collapse of the USSR, the Kazakhstan GDP was only 12 times greater than the Kyrgyzstan GDP. Nonetheless, it is still possible to compare them. To do so, we have used the World Development Indicators (WDI) statistical database collected by World Bank.

It is a huge data file that consist of thousand different indexes given in the real-time mode. The fact that it is collected and published according to the one-size-fits-all countries program is the beauty of this collection. It gives one an opportunity to perform a comparative analysis of many different countries. For our purposes, we have compiled a small but very emblematic table of different indicators. The further argument is based entirely on the analysis of this data.

Peoples Trade vs Resource Monsters

The economic structures of the two neighboring states are drastically different.

The portion of the added value produced in the aggregate sector of the real economy in Kyrgyzstan (which, according to the WDI database, includes agriculture, manufacturing output, and trade) is significantly higher than in Kazakhstan’s real economy.

On the other hand, it is dramatically lower in the industry – the sector dominated by the mineral resources extraction. It is precisely this sector that makes the modern Kazakhstan economy an economy of scale and enables the country to position itself as a major nation. One of the most important features of the resource economy is the extreme concentration of the capital and the distribution of the produced added value profits among a narrow circle of people who can act as they see fit.

Trade is Kyrgyzstan’s economic generator. Its portion in the country’s GDP is significantly higher compared to Kazakhstan. Its role in the Kyrgyzstan economy correlates to the role the industry plays in the Kazakhstan economy. Mostly, the trade in Kyrgyzstan consists of importing goods and services. Based on the statistical data, this import goes to satisfy the domestic demand since the current account balance in the country is negative. However, considering the Kyrgyzstan practices, one may suggest that this import, then, makes its way to other countries through the unofficial channels.

The inter-temporal changes in the current account balance also support this hypothesis. These changes are directly linked to the economic situation in Russia. It is possible that the abnormally high level of the money transfers to the country indicates not only the number and the size of the salaries of the Kyrgyzstan citizens abroad (mostly in Russia) but also the payments for the import deliveries made through the unofficial channels.

This data indicates the “peoples’ nature” of the Kyrgyzstan market economy despite its “shadowy” character. In this sense, even as we speak, Kyrgyzstan represents an archipelago of the Silk road analogous to the European hubs that became the out-posts of the liberal market economy and the oligarchy political system. This constitutes its principal difference from the Kazakhstan economy the lion portion of which consists of the large investment projects working for the export markets and not affecting the lives of the overwhelming majority of the Kazakhs people.

It is interesting to estimate the dynamics of the foreign investments in Kyrgyzstan. During the first decades of its independence, the measure of the index (% of the GDP) had been miniscule in comparison to the large figures of the Kazakhstan data. However, in the recent years, the situation has changed dramatically and now it is Kyrgyzstan that is showing the larger figures.

In the absolute numbers, these indexes are, of course, incomparable. But the mere fact of the transformation of the “bazaar” market model into an investment-attractive one in the country without a large domestic market and an access to sea routes is quite impressive. It will not be much of an exaggeration to say that Kyrgyzstan is a true beneficiary of the new continental trade routes architecture promoted in Eurasia by China.

Import Duties vs Resources Rent

The differences in the economic structures of the two countries are reflected in the structure of the tax portion of their budgets.

The goods and services taxes are the main source of the state earnings in Kyrgyzstan. They constitute more than 40% of all the state taxes. In Kazakhstan, this index constitutes only 18%. The proceeds from the foreign trade is the predictable driver of Kazakhstan’s state earnings, it constitutes 19% of them all. In Kyrgyzstan, this index is three times lower and has a very different origin.

The import duties and other related charges are one of the most important parts of the budget earnings in Kyrgyzstan. They constitute 13% of all the tax earnings in the country. In Kazakhstan, the portion of the import duties constitutes the miniscule 5% of the total state earnings. This probably happens not because the government wants to impose taxes on importing goods to the country but because in cannot – the import plays a very significant role in the domestic consumption structure, so any changes in this sphere may lead to the negative social consequences. For this reason, this part of the income has remained stable during the whole period of collecting the statistical data recorded in the database for the past two decades (the statistics for the 1990s simply does not exist). However, there is one rather strange exception. In 2011, the portion of the import duties in the structure of all the state earnings grew by times reaching the mark of 16% but then, it quickly dropped again to the previous levels.

To replenish the budget, Kazakhstan uses the export channel. The export duties constitute almost a quarter of all the tax earnings in the country. Kazakhstan’s export nomenclature consists almost entirely of the primary products. Therefore, the export duties are nothing but a primitive instrument of extracting the rent money from the national mineral resources. It ends up in the budget and then is redistributed among different civil and political groups.

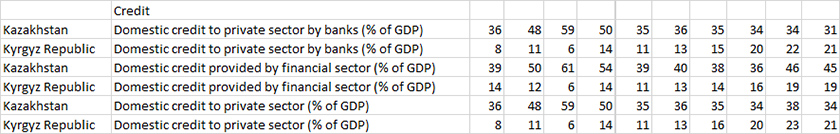

Such mechanism has come into existence relatively recently. Even as of 2004, the portion of the export earnings in the state budget structure amounted to 1%. Then, there were several years of data absence (which, in itself, is significant). In 2010, however, the portion of the export duties constituted 17% of the state earnings. Of course, the export rent had existed during the entire time of Kazakhstan’s independence, but, up to a certain point, it simply did not end up in the budget and was distributed over the economy through the credit channels. The budget consolidation had changed the rules of the game in a drastic manner and, essentially, destroyed the national credit system transforming it into the purse-bearing one (just like it used to be in the USSR times). The structure of the foreign trade and its important role in the structure of Kazakhstan’s state earnings is seriously limiting the country’s possibilities for reaching the classic goals of the macroeconomic regulation.

Kyrgyzstan does not know that the export tax is and a significant portion of the foreign trade earnings, due to the transit nature of the latter, does not end up in the budget. Nonetheless, the tax portion in the general structure of the state earnings in Kyrgyzstan is much higher than in Kazakhstan which reflects that Kyrgyzstan’s financial system is more oriented towards economic transactions and not towards the rent consolidation.

The Human Capital and the Future of the Countries

Kyrgyzstan’s economic system is primarily oriented towards the exploitation of the human capital and, therefore, critically depends on its quality. The portion of the salaries and other payments constitutes 41% of all the economy expenditures. In percentage terms, in Kyrgyzstan, the measure of this index is six times greater than in Kazakhstan where, on the other hand, the goods and services portion of the expenditures is higher comparable to Kyrgyzstan.

The data on the portion of the companies in possession of the international certificates speaks quite eloquently (albeit indirectly) of the level of the employees’ qualification. In 2002, Kazakhstan surpassed Kyrgyzstan in terms of this index, now, however, the ratio has changed, and radically so. Today, the portion of the entrepreneurs in possession of the international certificates in Kyrgyzstan exceeds the Kazakhstan data by almost 200%.

The human capital in Kyrgyzstan has one feature that, under the modern economic conditions, gives it a most important competitive advantage. Practically 40% of all the country’s city population lives in Bishkek. Essentially, Kyrgyzstan has the form of one megapolis surrounded by the areas incorporated into its economy.

At the first glance, this structure seems suboptimal. Nonetheless, this is exactly how the future of the civilization is seen by the contemporary urbanists who have buried the “global village” idea entirely and permanently.

The Energy/Geopolitics Cocktail

Kyrgyzstan’s main asset is water. First and foremost, as the energy source. Hydro-power stations generate 90% of all the energy in the country.

The energy independence gives Kyrgyzstan a significant competitive advantage in the situation when the access to the energy resources has become an operating tool for the trade and political diplomacy. Moreover, the hydropower industry enables the country to become an energy exporter. It is, however, still only a possibility. Any independent decision about the use of the hydro-resources may lead to conflicts with the neighbors who have a propensity to consider these resources the common property of the region. Therefore, for Kyrgyzstan, possessing a most important resource, from a potential advantage and an instrument of influence, has turned into a real problem.

Apart from the geopolitical risks, the development of the hydro-power industry in the country is restrained by the unclear investment prospects. The energy rate is nothing but an object of political bargaining. The presence of a wide specter of the political forces makes this bargaining even more intense and the energy tariffs – ones of the lowest in the region. Even after the recent increase, they remain two-four times lower than those in Kazakhstan (that, in their turn, are significantly below the Russian rates).

The situation is worsened by the massive energy losses in the country. Routinely, these losses are explained away by the poor state of the network maintenance, however, other factors, too, can be in play. (There is every likelihood that both private households and businesses connect to the energy sources independently). The dynamics of the losses indicates this as well. The losses grew from 16% in the beginning of the 1990s to 37% in the beginning of the 2000s and then dropped to the current 24%.

Kyrgyzstan’s strategic energy dilemma, therefore, goes as follows: the possibilities do exist, but the practically realizable initiative is absent. The geopolitical and the domestic political factors prevail over the investment interest. For this reason, the Russian projects of building several hydro-power stations announced in 2012 had failed. And now, the Russian official representatives are promising to enforce the damages suffered by the Russian companies.

Up to the recent times, the regional structure of the power-networks built in the Soviet times did not allow Kyrgyzstan to create a closed national energy-supply system. The deliveries to the northern regions had to go through the Kazakhstan networks. In 2015, thanks to the new electric transition line, Kyrgyzstan was able to resolve the question of supplying the power to the northern part of the country. As a result, despite the general problem of the energy deficit, Kyrgyzstan decided to back out of purchasing the electric power in Kazakhstan not being able to negotiate the prices.

Now Kyrgyzstan is planning to buy the electric power in Tadzhikistan that, as we know, has the strongest hydro-energy complex in the region. This will invariably lead to forming a regional bloc of the states oriented towards the use of the hydro-power. This bloc will be in opposition to the countries that seek to use the regional water reserves for the agricultural purposes.

Kazakhstan’s position is a special one. Coal firing constitutes more than 70% of the electric power produced in the country. This structure was formed in the Soviet times and, during the decades of Kazakhstan’s independence, had not undergone any serious changes. Moreover, it has the unlimited possibilities for growth (under the condition that this electric power will be purchased by the neighbors according to the tariffs that fit Kazakhstan).

Any regional hydro-power investment projects wreak havoc on the coal generated power of Kazakhstan thus putting the country in opposition to any such initiative. Therefore, the perspectives of the collective system necessary for solving the water and energy supply problem in the region, as of now, looks quite hazy. Just as the perspectives of Kazakhstan/Kyrgyzstan cooperation do.