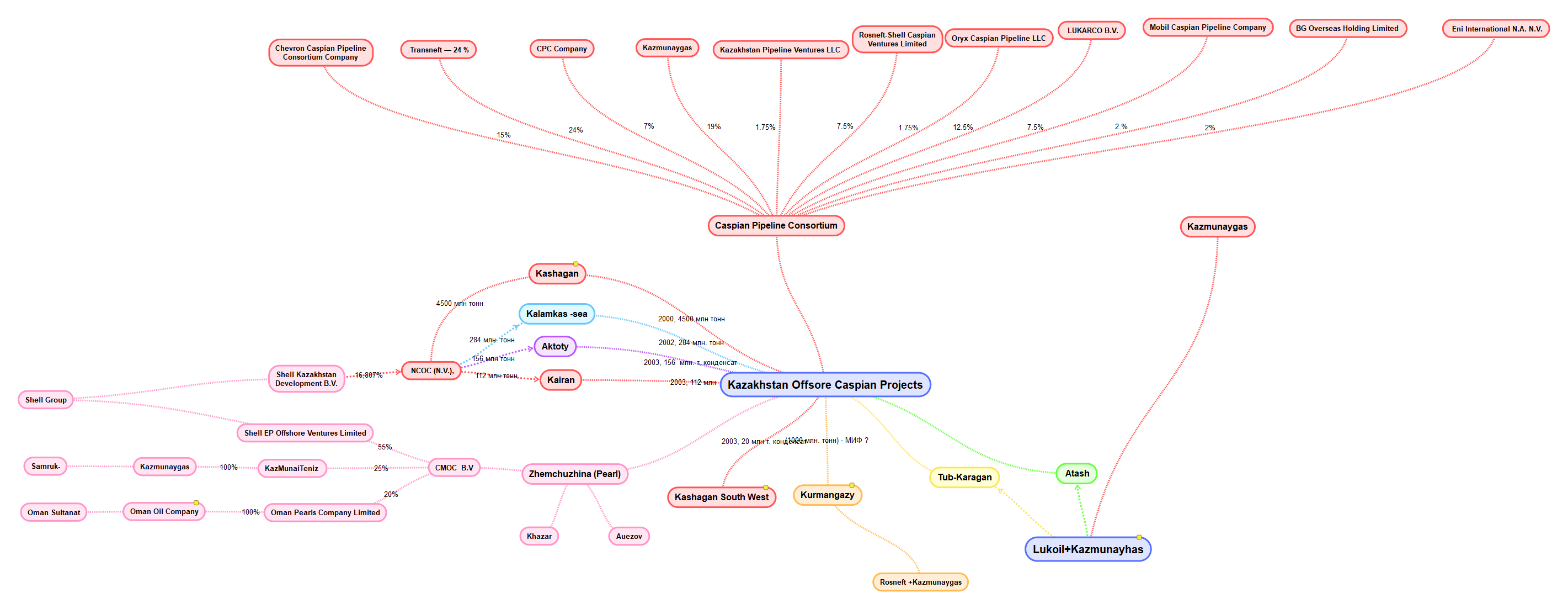

The transition in Kazakhstan is happening not only in the realm of the public affairs but in business as well. We are talking about the large-scale privatization of the “commanding heights” of the national economy oriented towards the resources export. The “correct” choice of the investors, as the Russian experience shows, guarantees ensuring the property interests of the family for at least a decade. Although, considering the process of selection, the national interests may suffer.

The fact that the Shell corporation has received an offer to buy a share of the capital from the KazMunayGaz Kazakhstan national company and is considering it was announced by a Kazakhstan financier in his Facebook blog (via a quote from Bloomberg).

The question for whom this deal would be most beneficial has not yet been answered. We have decided to sort out the situation that, in reality, turned out to be quite a difficult and a complicated one.

A “Pearl” in the “Shell”

The news on the offer to buy a part of KMG was revealed almost simultaneously with the information that Shell may strengthen its position in the main Kazakhstan oil project – Kashagan.

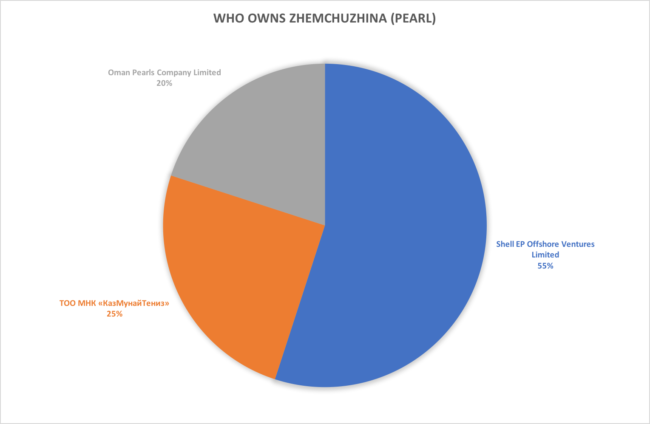

The strengthening will happen after including the Zhemchuzhina (Pearl) oilfields located in the Caspian shelf (not far from Kashagan) in the project. Shell is the majority shareholder of Zhemchuzhina.

Who Owns Zhemchuzhina

Both oilfield groups are being developed according to the modern version of the “concession model”. On December 14, 2005, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan signed a product sharing agreement (PSA) with the international consortium. It consisted of three participants – Shell EP Offshore Ventures Ltd, KazMunayTeniz International Oil Company JSC (100% affiliated with KMG) and Oman Pearls Company Ltd. A year later, on January 8, 2007, Caspi Meruerty Operating Company B.V. (project operator) was registered in the Netherlands. But if Shell’s share in the consortium constituted 55% (25% belonged to KazMunayTeniz, 20% – to the Oman company), then, in the operator’s capital, the Kazakhstan and the British shares were divided equally – 40% each. Nonetheless, the division of shares in operating companies is usually not made public and Zhemshuchina is considered Shells’ project, especially since, from the technological point of view, it is indeed the case.

According to the 2005 agreement, the consortium received the right for oil exploration at the Zhemchuzhina contract area for the period of six years (from 2005 to 2011). In 2011, the right was extended for two more years (to December 14, 2013). Then, it was extended twice – to December 14, 2015, and to December 14, 2017.

At the end of 2017, instead of presenting the results of the exploration (or yet another extension), the consortium website http://www.cmoc.kz disappeared from the internet. The last edit was dated November 16, 2017. We cannot find what exactly was edited – someone, very professionally and meticulously, purged all the website materials from the internet-archive. Only a page on the Shell Group website had been kept as a memento.

The “disappearance” of the operating company became clearer after we had learned about including Zhemchuzhina in the Kashagan project.

Formally, the decision was made due to the closeness of the Khazar oilfield (part of the Zhemchuzhina bloc) to the sea part of Kalamkas, an oilfield belonging to the Kashagan PSA zone. The North Caspian Operating Co. company (NCOC), the Kashagan operator, has the right to explore the three oilfields neighboring the “Big Kashagan” – Kayran, Aktota, and Kalamkas (the sea part). Only Kalamkas, however, presents a commercial interest.

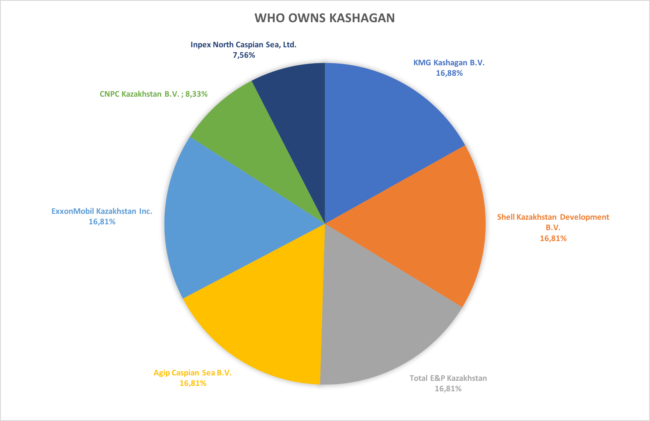

The “Shell” in Kashagan

What looks logical from the technical point of view, is in fact threatening to destroy the fragile balance of the Kashagan participants’ interests that has been achieved after a number of reshuffles and conflicts. Now the project includes the seven participants four of whom represent the interests of the leading Western private oil concerns (or the business-groups behind them). These are Shell Kazakhstan Development B.V., Total E&P Kazakhstan, Agip Caspian Sea B.V., and ExxonMobil Kazakhstan Inc. Each one of these four owns a share in the project capital that has been “calculated to a hundredth”.

Who Owns Kashagan

Any Shell strengthening may lead to a major conflict and, therefore, cannot be considered seriously by the authors of the on-going scenario. It is also unlikely that Shell, after all those years of exploration, would like to simply cash out making Kharaz a part of Kashagan.

The simplest scenario is to “promote” KMG’s interests. It can be done by lowering the project share (the state company owns the biggest share in the PSA). Or by buying a KMG share.

In reality, a combinatory takeover strategy may be implemented. In any case, the operative possibilities to pressurize KNG are now huge due to the recent arrest of the affiliated KMG Kashagan B.V. shares. Note that the shares were arrested based on the arbitration court’s decision following the claim of Moldovan investors Stati.

Read more on the Stati claim here – On the scandalous case of Stati and the coming catastrophe , On Freezing the National Fund’s Billions and the Stati’s Case, Akorda Is Risking Kashagan. Read on the Kashagan affair – The Grand “Sawcut” of Kashagan , Kashagan in Play!

Why does the “Shell” Need Kashagan?

Besides the “simple” oil interests, Shell has much bigger plans for Kashagan.

Apart from the two PSAs (Zhemchuzhina and Kashagan), the company owns 5.75% of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC). And, what is especially significant, only 1.75% of them are controlled via its affiliated company (Oryx Caspian Pipeline LLC). Another 3.75% are controlled via a joint venture company with a colorful title Rosneft-Shell Caspian Ventures Limited.

Note that CPC owns and operates the Tengiz – Novorossiysk oil pipeline that connects the Western Kazakhstan oilfields to the Russian coast of Black Sea from where the oil is exported to Europe via cargo carriers.

Of course, CPC is not a simple commercial enterprise. Initially, the pipeline was build for the purpose of excluding the Caspian oil from the system of the Soviet (Russian) pipelines which was accomplished successfully despite the fact that they were laid on the Russian soil. Moreover, its importance was not limited by the task to deliver the oil from the Tengiz oilfield to the Novorossiysk maritime terminal. It was supposed to be used for the Kashagan “big oil” as well. For this reason, there was talk that the initial throughput capacity of the pipe that constituted 28 mln ton a year was to be increased.

From the very beginning, this talk had taken the geopolitical turn of “who will control the tariff for pumping the Caspian oil through CPC”. As history tells us, the one who controls the tariffs, controls the price.

It may now sound like a historical irony, but Shell had grown to be an oil company thanks to… the Caspian oil. The founder of the company, British subject Marcus Samuel traded boxes of shells in London (the name of the company and its corporate brand are a tribute to this story) that he brought from South-East Asia.

The Samuel family could stay traders and sell trifles forever. But, like in any good story, the family managed to befriend the British Rothschilds who offered them to “trade a little oil” as well. This did not happen in London, it happened in Batumi where the Rothschilds were able to get a lucrative concession for building a railroad form Baku to Batumi that they bought from the broken-up authors of the idea. Samuel agreed and, soon, the barrels of the Baku illuminating kerosene (a prime oil product that was then in a big demand at the market) started being delivered to the South-East Asian countries – the main trading partner of the shell importer. As a result, the British Rothschilds sold their Shell business and quite timely, too – at the height of the WWI and on the eve of the revolution. After a couple of years, Shell had to face the Bolsheviks and was forced to say goodbye to its Russian business for a long time. But not forever, as it turned out.

Note that Shell entered the Salym project with the help of Shalva Chigirinsky, a person who also started his career by selling “trifles” (they usually mention Russian icons brought to the West from the USSR) and was very far from the oil business (and he still stays far from it fighting the US accusations of sexual abuse of a minor).

Shell’s “Caspian experience” of 100 years ago has finely demonstrated the main axiom of the resource market – the transiter and not the resource owner gets the last word. Shell’s main competitor, the Rockefeller Group, also rose at that time, following the “transportation wave”. The Rockefeller Group also managed to “set” (in other words, monopolize) a transport scheme. The founder of the US business “managed” to reach an agreement with the railroaders on giving a serious discount price to his companies (officially, they were not even affiliated corporations) that turned the business of his industry peers into a waste of time and money. Supposedly, a part of the discount prices later returned to the transportation companies which still did not help the bankrupt competitors.

By the looks of it, the agreement among the project participants had been reached. It can be inferred from the increase of the CPC oil deliveries. According to the results of 2017, their volumes reached the 55.1 mln ton mark which is 24.4% higher compared to the year 2016 (44.3 mln ton) and two times bigger than the initial throughput capacity allowed. Therefore, the planned 67 mln ton per year mark can be reached soon.

Today CPC is the main export route for the Kazakhstan oil. The question is which route will be the key one in the future. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline is CPC’s main competitor. This pipeline, together with the by-sea delivery, was supposed to be the alternative to the Russian pipe (even though it is not even included in the Transneft system). Supposedly, the volume of oil extraction in Kashagan will reach 11 mln ton in 2018, and this is just the beginning.

There are several ways to deliver the oil from Kashagan but, so far, it is unknown how they will be used. The only thing that is clear is that Shell has the obvious conflict of interests.

The ways to transport the Kashagan oil

By sea, the Kashagan oil will be delivered to Eskene, Then, it may be transported via the following routes:

the Azerbaijani – via the Eskene – Kuryk pipeline and then by tankers to Baku. From Baku, the oil will be transported via the Baku – Tbilisi – Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline to the Ceyhan oil terminal or via the “old” pipeline, from Baku to the Batumi oil terminal;

the Russian – via the Transneft networks and CPC to Novorossyisk and then, by tankers;

the Turkish – to Samsun, and then – via the Samsun – Ceyhan pipeline to the Ceyhan oil terminal;

the Balkan – to Bourgas, then, via the Bourgas – Alexandroupolis pipeline to the Alexandroupolis oil terminal;

the Chinese – via the future Kazakhstan – China pipeline or Eskene – Kenkiyak – Kumkol – Atasu – Alashankou.

The participation in CPC allows Shell to control both oil extracting and transporting. All the more so, since the main alternative route for CPC (BTC) is controlled by the British Petroleum concern – the life-ling Shell’s competitor. The BP state company created by the British aristocracy had to withstand the “common shell traders” and ensure the uninterrupted supplies of heating oil to the British fleet. BP was the first one of the large corporations that familiarized itself with the materials of the first oil exploration on the territory of the future Kashagan but, eventually, had to leave the project.

Apart from the fact that, Russia’s and Shell’s interests coincide in regard to this project, the company and the country are, in fact, connected even tighter. Shell is participating in the two biggest projects of the natural resources extraction in Russia. One of these projects, Sakhalin-2, by Shell’s representatives’ own confession, is the world-biggest complex development of the oil-gas deposits as well as one of the most complicated ones in terms of its engineering. The second one has to do with the development of the Salym group of oilfields. On the company’s website, it is called “the largest investment project of developing the oil deposits on the Russian soil with a foreign company participation”.

On the way to its successes, Shell had to live through a number of serious trials that resulted in the fact that the Gazprom Group became the company’s main partner in Russia (Gazprom – in the Sakhalin shelf, Gazpromneft – in Salym). It will not be an exaggeration to say that the fate of these projects will, eventually, be determined by Shell’s relationships with the aforementioned group.

What Does It All Mean?

So far, we do not have an inside on how Shell’s relationships with Kazakhstan are developing. Moreover, we dare to assume that, considering the complexity of the situation, any inside may, in fact, turn out to be a manipulation attempt. But the assembly of the already known facts lets us conclude that Shell wants not to simply participate in the KMG capital but searches for the ways to establish control over the individual projects that will, eventually, give it a possibility of the strategic participation in the management of Kazakhstan’s fuel and energy complex for decades to come.