Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan look quite differently not just in the news but on the maps of the political values and priorities as well. However, the data show how quickly the outlook may change. Just like it did in the Soviet Union of the 1980s.

We are continuing our presentation of a comparative analysis of the value matrix of the Kazakh population against other countries. This time, quite obviously, we have chosen to analyse the differences in the people’s attitude towards state authorities.

The revolution in Kyrgyzstan has brought the subject of the differences in the relationships between the people and the authorities to the agenda. The Kazakh intelligentsia that usually exists in the depths of social networks has moulded this subject into the form of a question — what separates us from the Kyrgyz people who, for the third time already, are throwing away the authorities in their country?

This questions is indeed important regardless of the assessment of the events and the possible future developments in this country. At this point, all the answers to this question possess exclusively speculative nature since they do not conduct regular population surveys in Kazakhstan. Hence it is especially interesting to look at the results of the surveys conducted in different countries with the use of a single program and methodology. This makes a comparison of different countries and civilisations not simply possible but quite objective.

Let us begin with what’s served as the starting point for the events in Kyrgyzstan — elections.

According to the last survey conducted by sociologists of different counties in accordance with the World Values Survey Association* program, the respondents’ opinion differ in a significant way (apart from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, we have chosen several other states for comparison).

* World Values Survey, WVS — a research project uniting the sociologists around the globe studying the values and their effect on the social and cultural life. WVS has conducted sociological researches in as many as 97 countries that constitutes about 90% of the population. All in all, from 1981 to 2017, the WVS had conducted as many as 7 rounds of research.

In Kazakhstan, the level of confidence in political elections registered by the sociologists is the same as the level of confidence in political elections in Germany. That is according to the respondents’ answers. At the same time, in Kazakhstan, elections themselves differ significantly both in terms of the procedure and the substance. On the other hand, the neighbouring Kyrgyzstan exists in a different realm as far as this issue is concerned. The number of the respondents that categorically distrust elections is critically high in this country. Quite strangely, in this regard, Kyrgyzstan is placed in the same category as the USA. Both countries are basically unified by one common feature — their political systems are undergoing a crisis and the presence of democratic systems pushes this crisis out to the streets.

Russia differs from all the previous examples in that it neither has the trust in democratic elections nor in their existence. This attitude can be described as cynical. This country does not trust in elections but it does trust in the leaders whom it perceives as guarantors. Basically, this model is close to that of Pinochet’s Chile (by the way, quite a few publicist of the 1980s were calling for it).

Contrary to Russia, Kazakhstan believes in such a system and, in this respect, is placed in the same category as Tajikistan (perhaps Kazakhstan’s other neighbours such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan could have ended up in the same category had they allowed the sociologists to conduct the survey in their countries).

This category can be called a «façade» or a «virtual» democracy. All in all, it is close to the Soviet political model where the Constitution contained the highest standards of a democratic political system (the 1936 Constitution didn’t even have a clear mention of the communist party in the systemically important articles of the document). In reality, however, no elections existed in the USSR.

As we know, the Soviet political model had gradually evolved into the late Soviet one where the cynicism towards the officially proclaimed democracy had reached such an extent that the system collapsed as soon as an opportunity presented itself.

What if a civil war is ahead?

Where can we place Kazakhstan in regard to this issue? Sociological surveys cannot provide us with an answer. We can only assume that the virtual democracy in Kazakhstan serves not even as a façade but as a convenient explanation for the people’s own benefit. Just like in the late Soviet Union, the people may fear the alternatives — what is going to happen to them if this system seizes to exist?

The topic «as long as there is no war» had pushed away other fears from the public domain and basically turned into the foundation of the late Soviet epoch. Nowadays, another kind of war — a civil war — is claiming the same status.

It is very indicative that they did not ask this question in Kazakhstan in the course of the latest survey albeit they did ask it when conducting the 2011 surveys. Back then, almost 60% of the respondents were afraid of a civil war, 42% of them — «very much so».

The structure of the answers of the Kyrgyz respondents does not differ significantly from the Kazakh «fear matrix». Nonetheless, as we can see, this does not preclude people from taking to the streets in Kyrgyzstan.

If we interpret the answers to the question about the confidence in political elections as a ritual one and consider the responses on the fears of a civil war as real expectations, we find ourselves right in the middle of the Soviet 1980s. When everyone had reason to experience fears.

In Russia, where the share of the «very afraid» citizens has grown thus demonstrating the escalation of fears, the trend looks particularly alarming.

Confide in the police

The concerns about the civil war in Kazakhstan do not contradict the high level of confidence in the police. At least, this follows from the responses. More than a half of the respondents expressed confidence in the police and a little more than 5% expressed open distrust.

In Kyrgyzstan, the number of distrustful people (i.e. really distrustful) is three times higher than in Kazakhstan. And now this ratio clearly demonstrates itself on the streets of Bishkek.

Considering the developments on the streets of yet another post-Soviet capital, Minsk, it is interesting to compare these data to the surveys conducted in Belarus. Their results fluctuate somewhere between Kyrgyzstan’s and Kazakhstan’s albeit are situated closer to the latter.

In other words, if we continue examining the situation in terms of the police domain exclusively, the events in Kazakhstan are more likely to unfold according to the Belarusian scenario and not the Kyrgyz one. But, in any extreme circumstances, this domain may quickly shrink to the territory of a couple of the capital city blocks.

Do you like parliamentary system? Sounds interesting

The existence of strong political institutions guaranteeing localising civil conflicts and transforming them into a tough yet political ones has always served as the main alternative to a civil war in any country and at any given time. Rephrasing the famous Clausewitz’ axiom, politics may be defined as a civil war fought by different means.

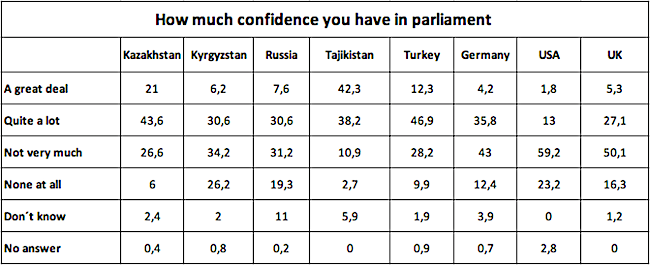

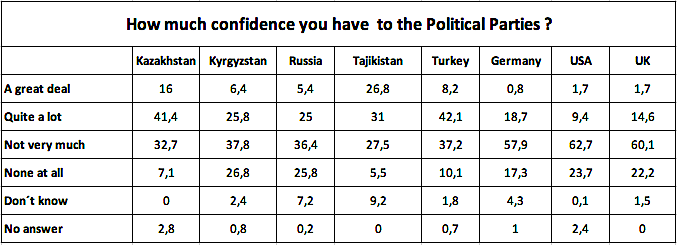

In this regard, the political outlook of the surveyed respondents from Kazakhstan looks particularly surprising. Most of them have a high level of confidence in the Parliament and political parties.

It seems as if the people are talking about completely different states — those with real political parties and parliaments. Paradoxically, it is in these countries (such as the UK) that the people tend not to trust in these institutions. Probably, because they know what they are like not from hearsay but from real life.

At this point, let us recall the famous expression of Winston Churchill who once defined democracy as «the worst form of Government except all those that have been tried from time to time.» This expression has become an idiom and begun living its own life. However, in reality, this saying has a much deeper meaning. Especially considering that the one who said it was not the omnipotent Prime Minister but an opposition leader who had just lost the parliamentary elections to a much less known and lacklustre character — Laborite Clement Attlee.

Here is Churchill’s saying in its entirety:

«Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time; but there is broad feeling in our country that the people should rule, continuously rule, and that public opinion, expressed by all constitutional means, should shape, guide, and control the actions of Ministers who are their servants and not their masters».

The saying looks so much more significant in its full form. Especially considering that Great Britain was fighting the war without suspending the work of the Parliament. The real Parliament.

The opinion of the contemporary British people who do not have a strong trust in either the Parliament or the Government seems to be in a full accord with Churchill’s definition.

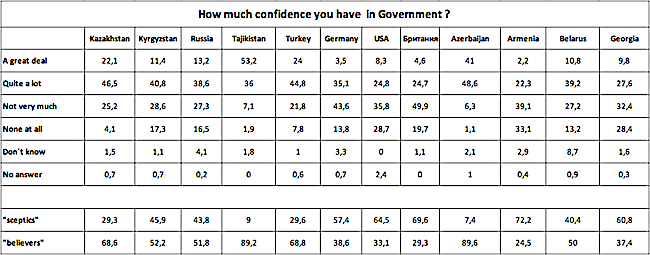

In Kazakhstan, the people have a very high level of trust in the Government according to the surveys. In Kyrgyzstan, this level is significantly lower albeit much higher than in the UK. Nothing surprising here: in general, the level of confidence in the Government is negatively related to the level of development of the parliamentary system of governance. Thus, in the UK, people understand that the government can always be replaced and see no need in cultivating confidence in it.

In order to demonstrate this trend in a clear way, we have divided the «sceptics» (those who do not have a high level of confidence) and the «believers» (those who have a high level of confidence or those who simply trust in the government) into two different categories. What we’re got is a clear political outlook of the world. The problem lies in the fact that the number of the «believers» in Kazakhstan rather reflects the outlook painted with eyes wide shut. And with a beatific smile on the lips.